Ireland's neutrality and proposed scrapping of triple lock 'entirely unrelated', Dáil committee hears

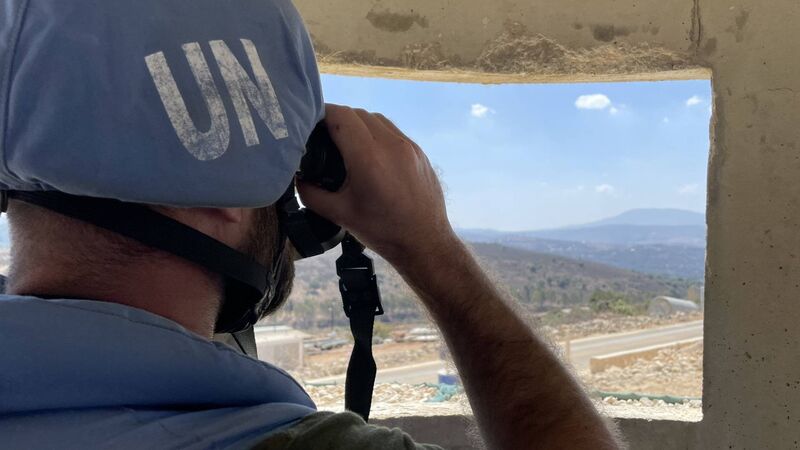

Current UN missions to Lebanon, which Ireland has been part of since 1978, were now in danger of not being renewed by the UN Security Council, Dáil told.

Ireland’s neutrality and the proposed scrapping of UN authorisation for future Irish peacekeeping missions are “entirely unrelated”, a former senior Department of Defence official has said.

Ciarán Murphy told the Oireachtas defence committee that there would be “absolutely” no change to Ireland’s neutrality — defined as non-membership of a military alliance — if the so-called ‘triple lock’ is removed.