'He had an incredible goodness in his heart': Dunnes strikers pay tribute to Desmond Tutu

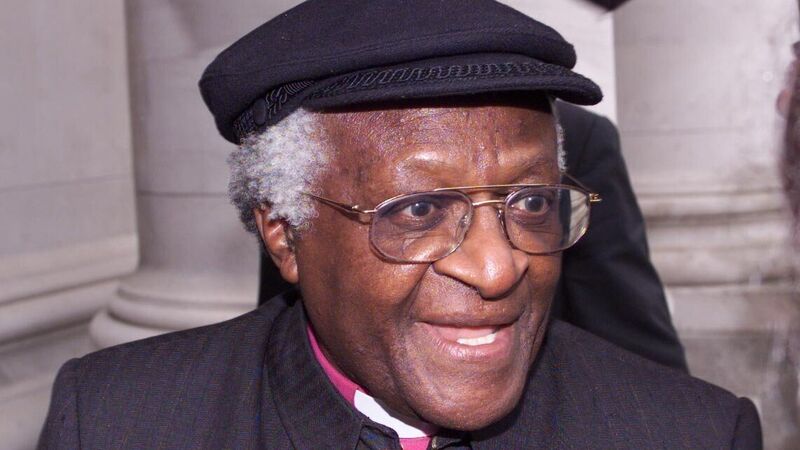

Archbishop Desmond Tutu at Government Buildings, during a visit to Ireland in 1998. File picture: Billy Higgins

Mary Manning was unsure and nervous. Archbishop Desmond Tutu had requested a meeting with her and other representatives of the Dunnes Stores strike while he was travelling to Oslo to collect the Nobel Peace Prize. How do you act in front of someone like that? What do you say?