State is responsible for several mass abuses, alternative Mother and Baby homes report finds

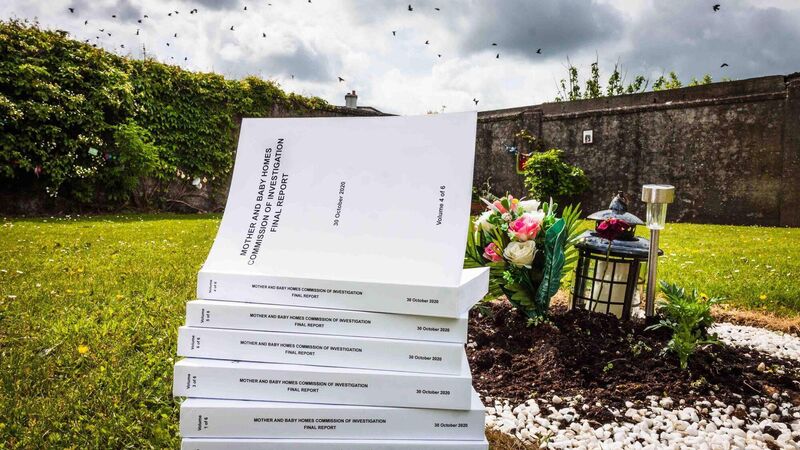

The official report of the mother and baby homes commission photographed at the site of the Tuam home. A group of legal and academic experts who 'profoundly disagreed' with its approach and findings have produced an alternative report. Picture: Andy Newman

The State is responsible for several mass abuses, including breaches of human and constitutional rights, an alternative expert report into mother and baby homes has found.

A group of 25 legal and academic experts have forensically examined the final report of the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes to come up with alternative findings.