Has GSOC’s strong hand become a heavy hand?

The Morris Tribunal into corruption by members of the force in Donegal had shown the weakness of the Garda oversight system, the old Garda Complaints Board lacking the necessary independence and authority to inspire respect among gardaí or confidence among the public.

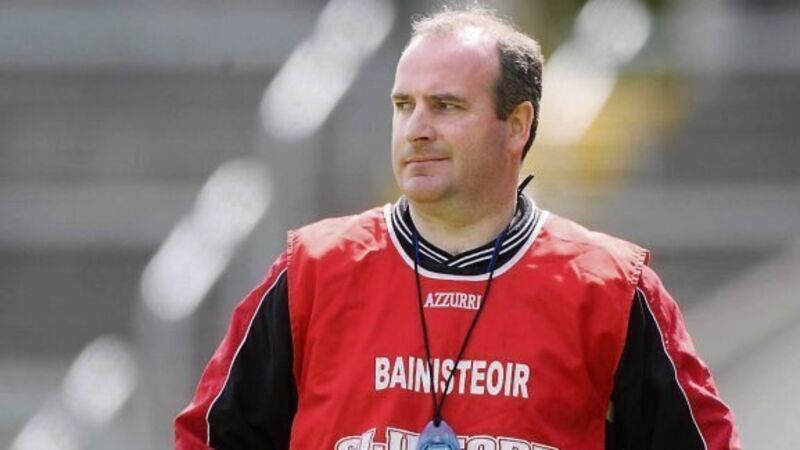

But the death of Sgt Michael Galvin raises questions over whether the strong hand that a body like GSOC needs to perform its work has instead become a heavy hand.