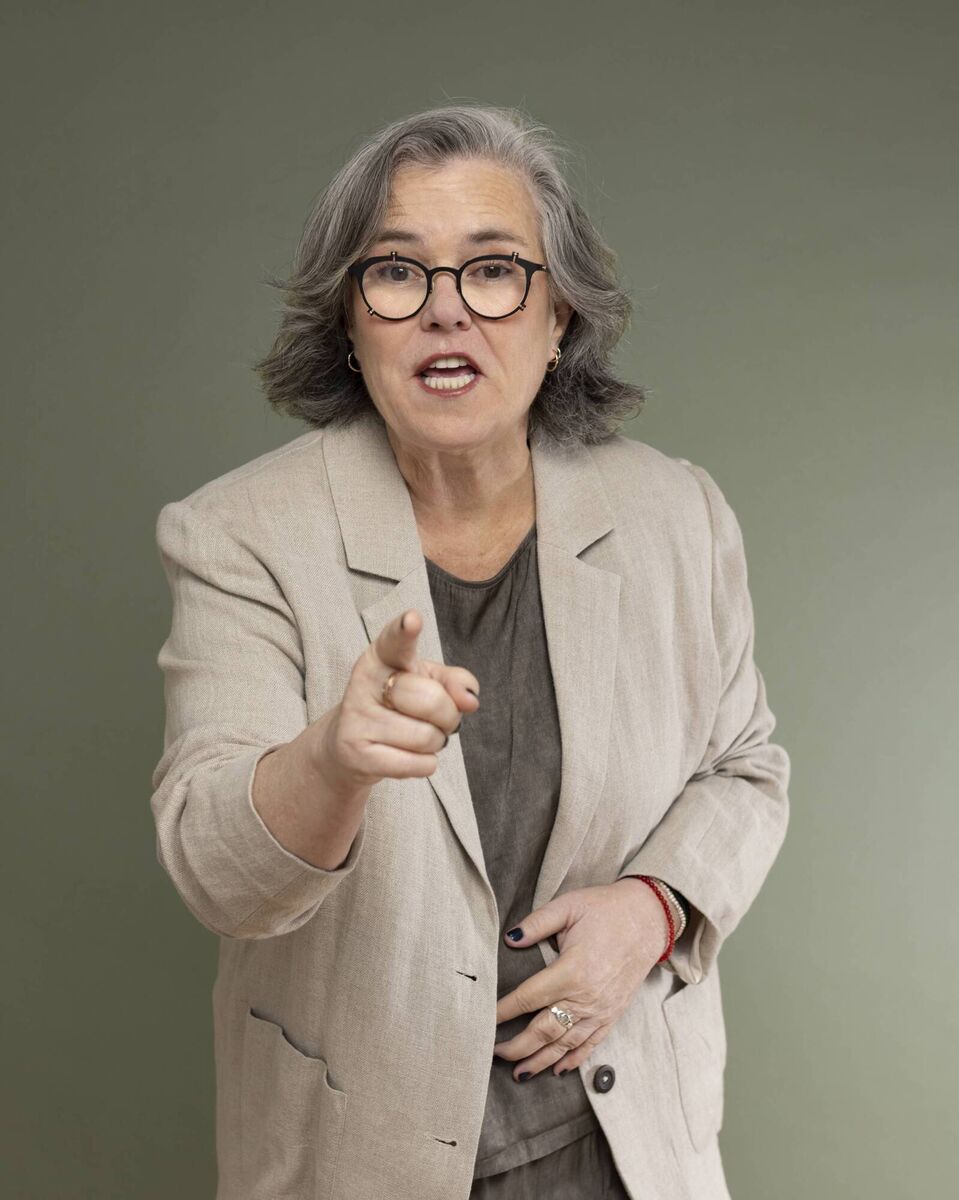

Rosie O'Donnell: 'It was very strange to feel so at home in a new country. But I do'

Rosie O'Donnell: “Everyone warned me about the weather, but you know what? I quite like it.”

If Irishness was measured by people’s ability to talk about the weather, Rosie O’Donnell may well deserve some sheep-grazing rights. Actress, activist, advocate, comedian — it’s hard to know where to begin with someone whose life has been so public for so long. So I take the soft approach. I choose rain.

I tell her I’m in the West, where the wet arrives like a nosy neighbour. Rosie is in Dublin. She laughs when I tell her that maybe, for once, things are a little drier out West than they are up East. “It’s funny,” she says. “Everyone warned me about the weather, but you know what? I quite like it.”

O’Donnell has been in Ireland for just over a year now. She moved here in protest at Donald Trump’s America — a decision that made headlines on both sides of the Atlantic, not least because of her long-running, famously personal feud with the most divisive American president in living memory.

Last year, he threatened to revoke her American citizenship. In March, she’ll bring her show to Cork Opera House, extending her return to live comedy after a 10-year break.

But before we get to Cork, or comedy, or Trump, we circle back to the rain. “The thing about the weather here,” she says, “is that even when it’s cloudy, it’s still not dark grey. The sky is like a white colour. In New York, when it’s cloudy this time of year, it’s so grey — and it’s very, very depressing.” In Ireland, she says, even the bad weather feels different. “I find that even when it’s raining, the light is always there.”

For all the political drama that framed her move, O’Donnell speaks about Ireland less like a celebrity in exile and more like a person who has landed somewhere that fits. She has been back to the United States recently — briefly, and quietly — to visit her older children. She admits she was anxious before she travelled.

“I was definitely nervous,” she says. “I wondered about what they were doing with people, looking at their Instagram and their TikTok.” She laughs, but there’s a hard edge to it. “I thought, well, if they look at mine, I’m not getting in.” Normally, she says, she’d go to Broadway, to restaurants to eat with friends. This time she didn’t.

“Just because things are so volatile,” she says.

In America, she describes a tension that exists alongside denial — crisis and spectacle in the same breath.

“You’re there, and you’re watching … ICE killed someone else, and this story, and that story. And yet then, suddenly everything is about the Golden Globes: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, here is so-and-so dressed in a $155m dress.’” The disparity is what unnerves her.

“There’s sort of like … a disconnect between the perceived reality and the reality that’s actually happening,” she says. “It’s like you’re living there in both ways.”

Since moving to Ireland, she’s stopped watching American news. “In America you can’t get away from the news,” she says. “So I felt very bombarded by all of the trouble that’s happening.” O’Donnell didn’t announce her move in advance. “We just kind of showed up,” she says. “We just sorted all our papers in order and came.”

She arrived without work lined up, without a plan. “When I got here, I didn’t know what I was going to do,” she says. “I thought, well, I’ve got to be working on something while my daughter’s at school. I can’t just sit home and do nothing.” So she started writing.

That writing became the show she’s now touring: A one-woman piece that threads together comedy, grief, motherhood, and the mistakes you only fully understand once your children are grown. “It’s funny,” she says, “because for many years I’ve been trying to write one about my mother, and my mother’s death, and how that affected my being the mother of five as well.”

Her mother died when Rosie was a child — a loss she has spoken about for decades, and one that still sits close to the centre of her. In Ireland, she says, something in her settled. “Now that I’m going to be 64,” she says, “I got here and I was surrounded by this Irish culture that I grew up heavily invested in.”

She’s Irish-American by heritage — “100% Irish, according to 23andMe,” she says — and her family’s identity was always steeped in it. Being here, she didn’t expect to feel so at home. After her mother’s death, her father brought the family back to Ireland for a time, visiting relatives.

It was the only meaningful stretch she’d spent here — and yet decades later the sense of recognition returned. “It was very strange to feel so at home in a new country,” she says. “But I do.”

The decision to leave the US wasn’t framed as an adventure. O’Donnell speaks about it as a necessity. She had read Project 2025, the hard-right policy blueprint associated with a second Trump presidency, and she says what she saw there made the decision for her.

“I read what their plans were — most of which have been implemented already,” she says. “And it was so terrifying … so I thought, I don’t have a choice.”

Her daughter, she says, is autistic, non-binary, and 12 years old. “I didn’t have a choice but to move and to take my child with me,” she says. She doesn’t hide her privilege. She moved, she says, because she could afford to. But when she talks about what the move has changed, she becomes most emphatic about one thing: school.

In America, she says, autistic children are often separated out of the mainstream system. There are private schools, specialist schools, and in her case, an LA school for neurodivergent children that cost $85,000 a year.

“Now what do you do,” she asks, “if you’re not a rich famous person and you have an autistic child or two? What does one do in America?” In Ireland, she says, she was shocked by what she found. “When I was looking for a school here, I was shocked to find a school that is a public school, which costs me nothing but hot lunch fees.”

Compared to $85,000, it felt unreal. And, crucially, her daughter is thriving. “She’s thriving in it,” she says. “And it’s not only autistic kids.” This matters, she explains, because “the world is not just going to be filled with people like her.”

“The world is full of all kinds of people,” she says. “And they have to figure out how to deal with [each other] … as part of being alive.” Her voice softens when she talks about her daughter’s response to the move.

“She made me promise that we wouldn’t go back until she’s done with high school here,” O’Donnell says. “And I promised her that.” If her daughter has found something in Ireland that feels safer, O’Donnell has too.

She gives me a small, vivid scene. She and her daughter go to a local pub once a week for a burger. In the summer they sit outside in the beer garden. Her daughter plays with other children and the parents treat Rosie like any other parent at the next table. After a couple of hours, as everyone was leaving, the other parents finally said something. “By the way,” they told her, “we’re big fans.”

O’Donnell was struck by the fact they’d waited. “I said, ‘You didn’t feel the need to bring it up while our children were playing?’”

And they said: “That’s not the most important thing.” When people do stop me, it’s not intrusive,” she adds. “They’re always apologising. They always say, ‘I don’t mean to bother you.’”

Then she laughs. “If you knew the difference between living in America and being a famous person and living in Ireland, you would know there’s nothing anyone in Ireland can do that could bother me — comparatively.”

The Cork show is rooted in parenting — not in the sentimental “aren’t kids wonderful” sense, but in the darker, funnier reality of trying to raise children while carrying your own history. When I ask about breaking cycles — about over-correcting — she answers instantly.

“I didn’t come from an ‘I love you’ family,” she says. “No one in my family ever said ‘I love you’ to each other.”

She had never heard the phrase until she was about six years old and overheard it in a neighbour’s house.

“I heard the neighbour saying goodbye to the daughter,” she says. “‘Honey, I love you. I’ll see you at dinner.’ And I was like … ‘I love you?’ What the hell?”

So she overdid it with her own children, trying to create the childhood she wished she’d had. But she admits to having clarity now — the hindsight of a parent whose children are adults — to see the flaw in that.

“That fantasy is not necessarily what an actual child needs. I made the road too smooth in front of them,” she says. “Trying to redo the childhood that I had.

“We know where life can take us,” she adds, “through pain, and through love. And both of those things are connected. We can’t have one without the other.”

O’Donnell’s activism isn’t a phase or a branding exercise. It has been consistent for decades — from LGBTQ+ rights to anti-war activism, from gun control to Palestine. When I ask her about the cost of speaking out, she frames it in historical terms. “You’re worried about the McCarthy era. Which is kind of happening now ...

“The people that I’m friends with who I admire so much, who use their voice to stand up for injustice wherever they see it — they’re the people that I respect the most,” she says.

Why don’t more people speak up?

“People are afraid,” she says. “They’re afraid of what’s going to happen to them.” She names Mark Ruffalo as someone she admires. “He inspires me,” she says. “He reminds me we need to keep going, keep pushing back.”

And she pushes back against the idea that public figures should stay in their lane.

Her Irish citizenship process, she says, should be completed soon. “We’ve been here a little over a year, so it should be coming in the next few months for sure.”

“I can’t wait for it,” she adds. Her grandparents were from here. Her father’s family retained a deep Irish identity even in America. For her, the passport feels like formal recognition of something she has carried all her life.

“I feel a connection to this country in a deep and meaningful way,” she says. “And I will be thrilled to have an Irish passport.” As we finish, she tells me she’s used to the questions about Trump — the American circus that follows her no matter where she lives now.

“I’m used to it,” she says. But she doesn’t sound defeated. She sounds steadier. Ireland hasn’t removed the chaos of the world. It has simply put an ocean between her and the daily bombardment of it. It has given her daughter a school where she belongs. It has given her, unexpectedly, a sense of home.

Even the rain hits different. Because even when it’s bad, she says, it doesn’t feel so dark.

- Rosie O Donnell — Common Knowledge is at the Opera House Cork on March 29. corkoperahouse.ie