The Good Mood Dude: Why a Jolly outlook is crucial for children's wellbeing

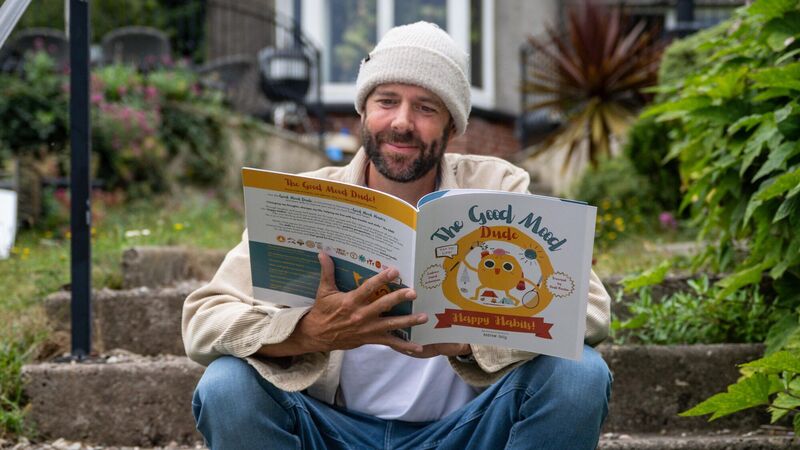

Andrew “Andy” Jolly, pictured here, has created Good Mood Dude, a self-help book designed to support children in managing their emotions. Picture Chani Anderson

Children see “the wonder in every stale thing”, a trait observed with both envy and admiration by the poet Patrick Kavanagh. Childhood is a time of wonder and innocence, when the seeds of resilience are sown. Andrew Jolly’s book The Good Mood Dude: Happy Habits reads like a manual on how to nurture those seeds and protect the joy we feel so effortlessly when we are children. The book equips children with tools to navigate life when it emotionally overwhelms.

What inspired the book? Jolly says: “For nearly 10 years, I’ve been teaching ‘happy habits’ in schools and, during assessments, I noticed that while students grasped the concepts, they struggled to articulate them.” So he began creating memorable mantras — like, ‘What you focus on, you feel’— to make the ideas stick.