My Life with Jim O'Sullivan: ‘Nothing could have prepared me for the Spike Island Prison riots’

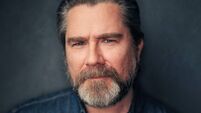

Jim O’Sullivan standing in front of a large framed photograph of Spike Island, where he served as a prison officer during the riots. Pictures: Chani Anderson

It started off like any other night shift in Spike Island prison before the unthinkable happened and inmates escaped in their droves.