Spooky Irish stories on Halloween - and the people who tell them

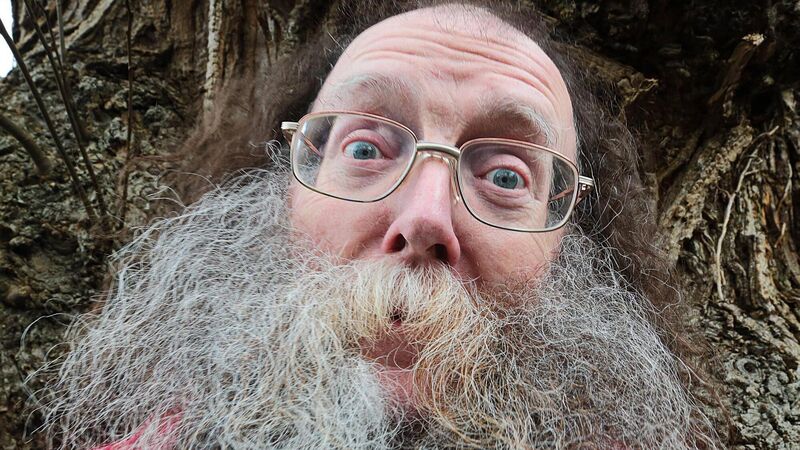

Seanchaí Eddie Lenihan:

“Halloween is the changeover time of the year, the time between autumn and winter, the Celtic end of the year. It’s neither this nor that, and anything might be expected to happen,” says seanchaí Eddie Lenihan.

Traditionally, it was a night to take a dare. “If you weren’t good at something, ‘twas the perfect night for going under the briars. Where I live in Crusheen, Co Clare, if someone has terrific luck at cards, they’ll say ‘Jaysus, were you under the briars last night?’” he says, before explaining what kind of briars you need.