Pest project planned for Lambay (Island)

View of Lambay from Donabate Beach, Dublin

Lambay lies 4km off the North Dublin coast. The ‘ay’ in its name comes from old Norse meaning ‘island’. This 260-hectare remnant of an ancient volcano, therefore, should be called ‘Lambay’ and not ‘Lambay Island’. Grounded on diverse igneous rocks, and rising to 127 metres above the sea, it supports both our most loved mammal and our most hated one.

Rabbits, once an important source of food, were introduced to Ireland by the Normans. Semi-domesticated, they were kept in warrens, often located on islands. Being selective grazers, they can reduce plant diversity. But the playful bunnies are not ‘all bad’. They dig burrows which they rent out to nesting seabirds such as puffins.

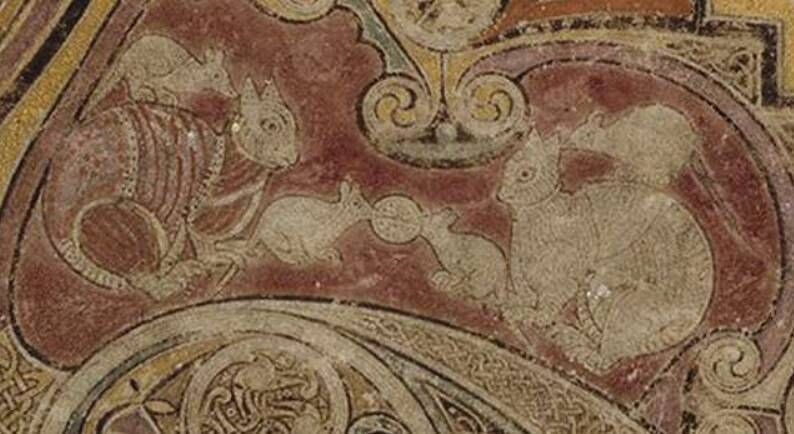

The ‘black’ or ‘ship’ rat — an unwelcome visitor to our shores — probably arrived in Ireland during the Dark Ages. The Chi-Rho page of the Book of Kells, created around AD800, shows two cats holding the tails of rats to prevent them from attacking a communion host.

Following a shipwreck in 1918,’ black’ rats took refuge on Lambay. By then, the black species had become very rare in Ireland, having lost out to the ’brown’, or ‘sewer’ rat, a Far Eastern native which arrived in Ireland around 1822. The black species is now confined to major ports but, according to Dr Matthew Jebb, descendants of the ship-wrecked ones still survive on Lambay.

The black rat is smaller slimmer, and has larger ears, than its ubiquitous cousin. Despite the name, it is more often brown or grey than black. Its nose is more pointed. The tail and whiskers are longer. More elegant than the brown one, illustrations of rats in cartoons and children’s books usually feature the black species.

Few creatures had such a profound effect on human history as the black rat. Although it is now Ireland’s rarest wild mammal, it once invaded dwellings and nested even in mattresses and bedclothes. This intimacy led to the spread of plague, which halved Europe’s population in the 14th Century. Brown rats, being more discreet, usually remain outside.

But the squatters’ days are numbered. A ‘Lambay Life’ project aims to rid the island of all invasive species, including the rats.

Seabirds will welcome this declaration of war. Lambay supports an internationally important seabird breeding colony. Rats take eggs and kill nestlings. They are a threat to the smaller seabird species, and to waders such as oystercatchers, breeding on the island.

But eliminating the pests humanely won’t be easy. Rabbits and rats have enormous reproductive capacities. Their populations bounce back quickly from adversity. Introduced to Australia in 1788, a rabbit population explosion there was out of control by 1867. Even the famous ’rabbit-proof fence’, erected in Western Australia failed to control their spread. It took the introduction of myxomatosis to put a stop to their gallop. There are up to two million rabbits in Australia today.

The rat is another loose cannon. A Malthusian-style rat population explosion might lead to mass starvation but rats would soon recover. Females become sexually active when just two months old and can produce litters of up to nine ‘kittens’ almost monthly. Eliminating such a resilient pest will be a tall order.

- Matthew Jebb. Lambay Life, an EU LIFE sub-programme project proposal (Jebb@gmail.com)

![<p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p> <p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p>](/cms_media/module_img/9930/4965053_12_augmentedSearch_iStock-1405109268.jpg)