Richard Collins: Black Death myths challenged in new research paper

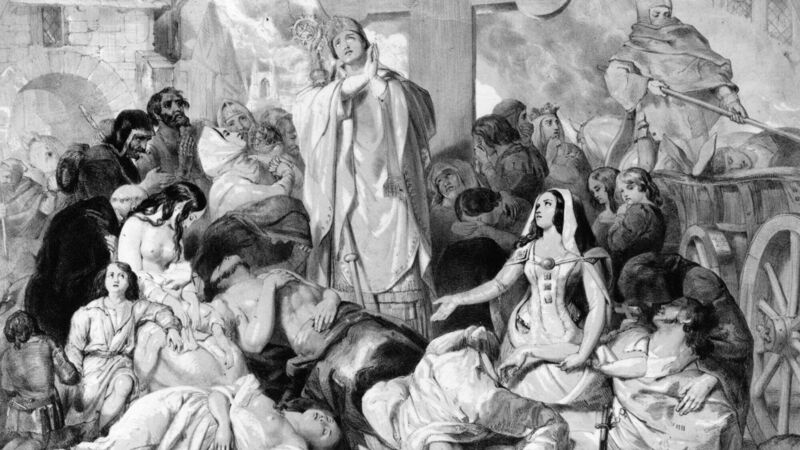

New research reveals that long-held beliefs about how the Black Death swept rapidly across Asia originated from a centuries-old Arabic literary tale, not historical fact. Image: People praying for relief from the bubonic plague, black death. Designed by E Corbould, litograph by F Howard. Picture: Hulton Archive

"What does it mean, the plague? It is life that’s all" — Dr Rieux in by Albert Camus

The Black Death ravaged Europe from 1346 to 1353. More than fifty million people — half the continent’s population — died.