Clapper bridges and stones with healing powers — stories of our ancestors, hidden in the Irish landscape

Clapper Bridge, known locally as Ros a’Locha Stepping Stones, County Cork, was the first bridge erected across this river (Abha na Sróine) Featured in Remnants of Our Past by Deirdre O'Neill

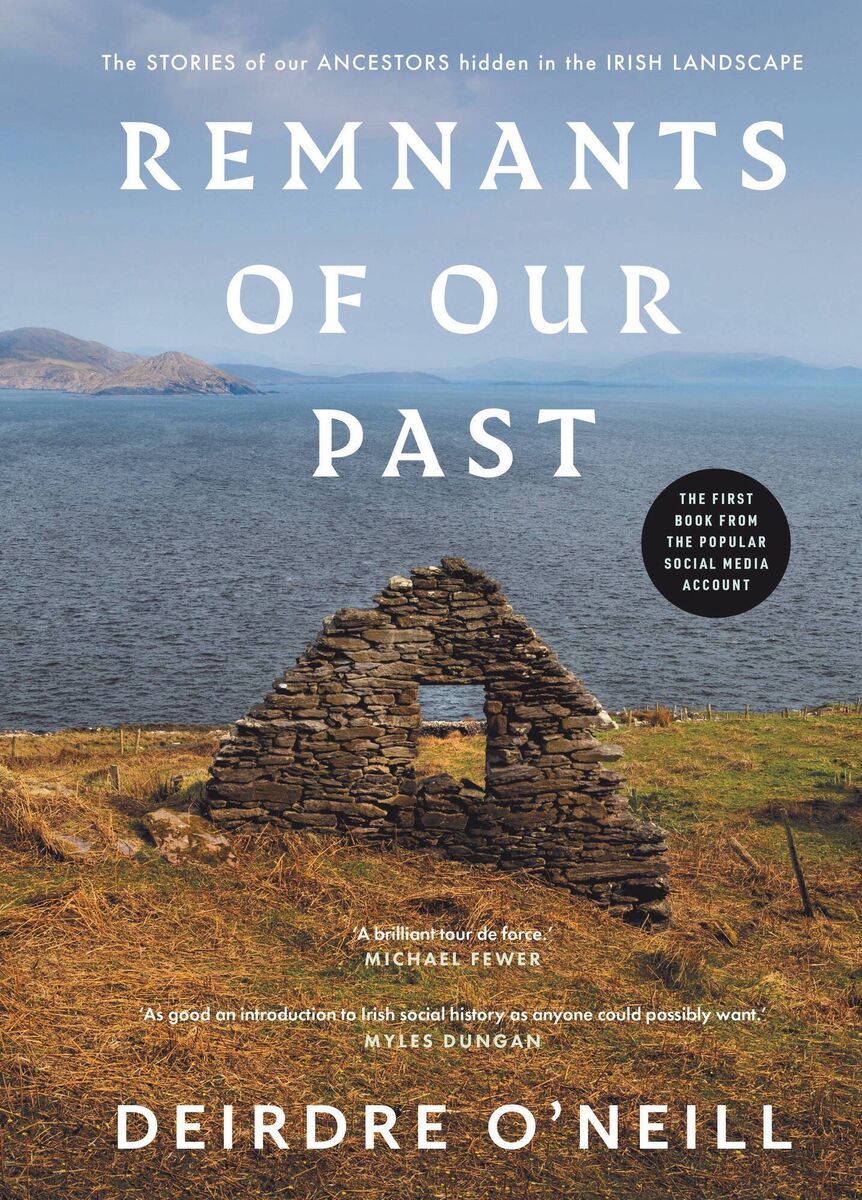

During lockdown while out on a walk, Deirdre O'Neill noticed metal rings on the wall of a church in Porterstown, County Dublin. She took a photo, posted to her Instagram and didn’t give it another thought. The next morning she was surprised by the huge reaction to her post. From then, she started looking out for these artefacts from our history, which we walk past every day without noticing. As lockdown eased and ended she went further afield and the account continued to grow and grow as Deirdre noticed more and more artefacts and researched their history. Today the account has more than 232,000 followers. The book expands on this project, and includes an artefact from nearly every county in the country. Deirdre uses these remnants to explore how people in Ireland ran their households, farmed, fished, entertained themselves, and honoured their dead.