Once 'sustainable' mackerel stocks are drastically declining

Anja Murray: "The future of mackerel in the North East Atlantic depends on human cooperation, between scientists and the fishing industry, and between governments of the countries that have traditionally benefited from mackerel."

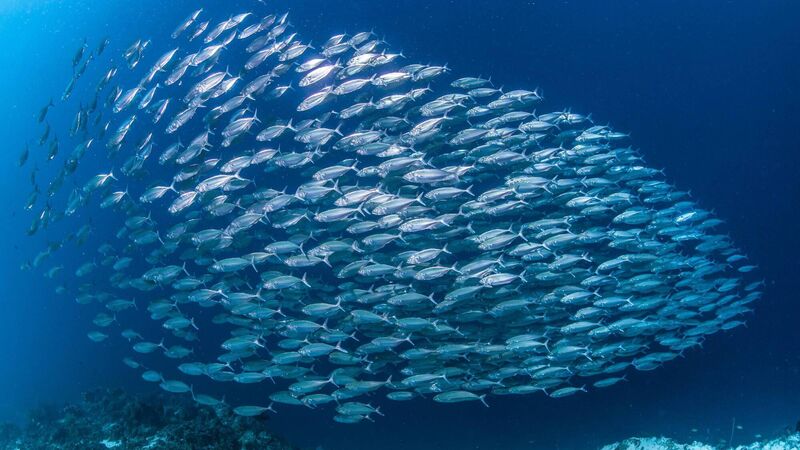

Mackerel are a striking fish. Adorned with dark wavy lines against shimmering blues and greens, patterns that have evolved to enable mackerel to shoal together in tightly packed schools.

Reflective platelets on key parts of their bodies allow mackerel to sense subtle changes in their neighbours’ speed and direction. If one fish overtakes another, the crystal-lined stripe appears shorter; if a neighbour swims upward, the line dims. This refined visual system enables vast schools to move as one, shifting shape in stunning synchronicity.