Ancient fights and double-dealing politics — a visit to Boyne battle site

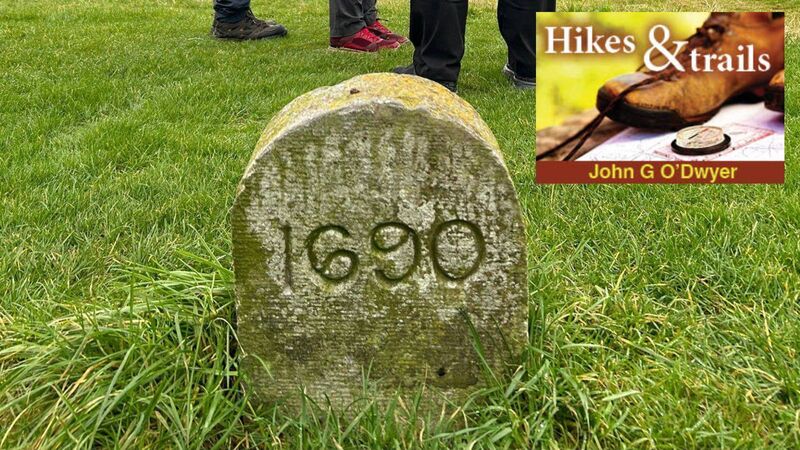

Schomberg Memorial, Oldbridge, commemorates the spot where the Duke of Schomberg died in the Battle of the Boyne. Pictures: John G O'Dwyer

More than 30 years ago, I journeyed with few expectations to the Battle of the Boyne site near Drogheda and yet returned disappointed.

There was almost nothing to suggest where or how the battle unfolded. This wasn’t surprising since Northern Ireland’s Orange Order had, for centuries, proclaimed the outcome a great victory for King William III against what they termed the threat of Popery in Ireland. By a country mile the largest and most significant battle fought on Irish soil, it ensured that, thereafter, only a Protestant monarch would reign on the British throne.

![<p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p> <p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p>](/cms_media/module_img/9930/4965053_12_augmentedSearch_iStock-1405109268.jpg)