'If you see me, weep': What Ireland's dry spell can learn from history's dry past

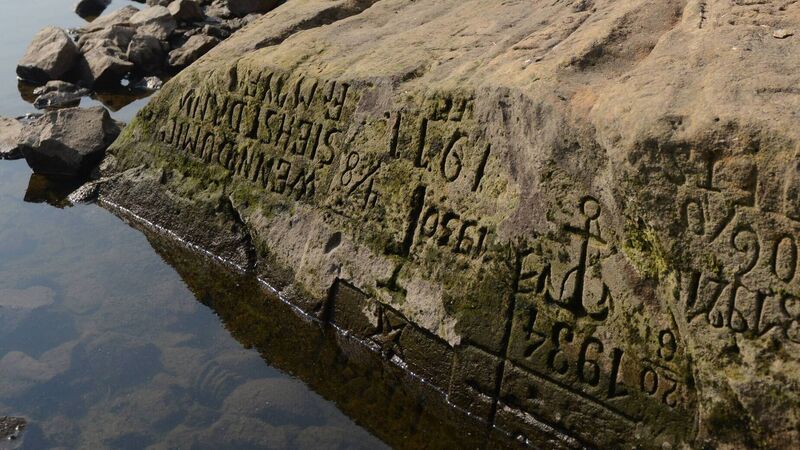

'Hunger Stone' at Decin, Czech Republic revealed by the low water level of the Elbe river — seen here in August 2018. Picture: Michal Cizek /AFP via Getty Images

Let’s face it, we’re not known for scorching summers (or springs). A few days of sunshine and suddenly the lawn is scorched, the dog is panting, and half the country is panic-buying paddling pools like they’re PPE in the pandemic.

But as May 2025 brings prolonged dry weather, with water restrictions looming, our green island is showing signs of thirst. History warns us to take it seriously. Droughts have reshaped civilisations across the world — and Ireland, despite its rainy reputation, isn’t immune.

Check out the Irish Examiner's WEATHER CENTRE for regularly updated short and long range forecasts wherever you are.

![<p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p> <p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p>](/cms_media/module_img/9930/4965053_13_augmentedSearch_iStock-1405109268.jpg)