Richard Collins: Study on childhood trauma in gorillas and chimpanzees

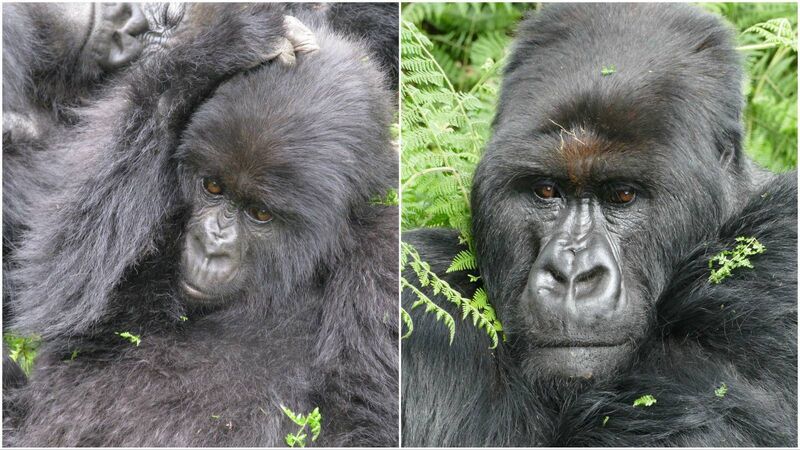

Segasira (shown as a youngster on left) lost his mother and father before the age of 4 but has recently established himself as the leader of a group at the young age of 17. Picture: gorillafund.org / Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund

Between October 1944 and May 1945, the German occupiers cut off food supplies to the western Netherlands. Between 18,000 and 22,000 people died during what became known as the Dutch Hunger Winter. There were also long-term effects. Children of women who were pregnant during the famine developed diabetes, obesity, and heart disease later in life. Grandchildren, in turn, were smaller at birth and more vulnerable to illness.

"The negative effects of early life adversity have been documented in a wide range of species from fish to birds to humans," note the authors of a paper just published. Researchers at the University of Michigan say that wild creatures, traumatised as youngsters, tend to have reduced life expectancies and produce fewer offspring. However, the effects of ‘early life adversity’ are complex.

![<p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p> <p> The International Union for the Conservation of Nature says that “an ecosystem is collapsed when it is virtually certain that its defining biotic [living] or abiotic [non-living] features are lost from all occurrences, and the characteristic native biota are no longer sustained”.</p>](/cms_media/module_img/9930/4965053_12_augmentedSearch_iStock-1405109268.jpg)