Behave like pigs in your garden to attract robins

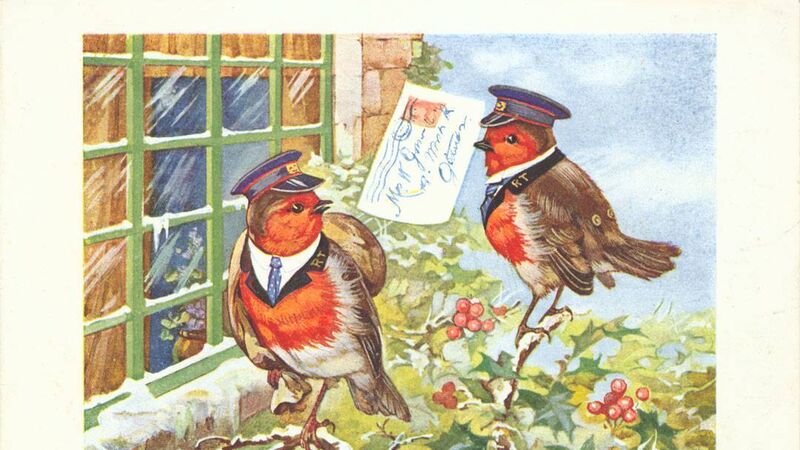

Robins may be associated with Christmas due to a clever 180-year old marketing campaign. 'The Christmas Morning Post'. London: Raphael Tuck & Sons, 1934. National Museums Liverpool

Robins are not at all shy of humans. We love to see them and tend to smile at their compact carriage, cheeky manner, and puffy red breast. But what we often take to be an inclination for companionship — the robin who follows us in the garden or down the lane — is in fact, a robin attached to his territory and who is keenly aware that we present potential opportunities for food.

Each brave little robin who hops from branch to branch alongside us is astutely keeping a close eye on us. From the perspective of a robin, humans are agents of disturbance: we might go digging in the garden, chopping back some plants, or moving buckets about. Each time we do so, wriggly worms are exposed, the perfect opportunity for a robin to jump in a gobble them up quickly.