Donal Hickey: Looking at life from a bat's point of view

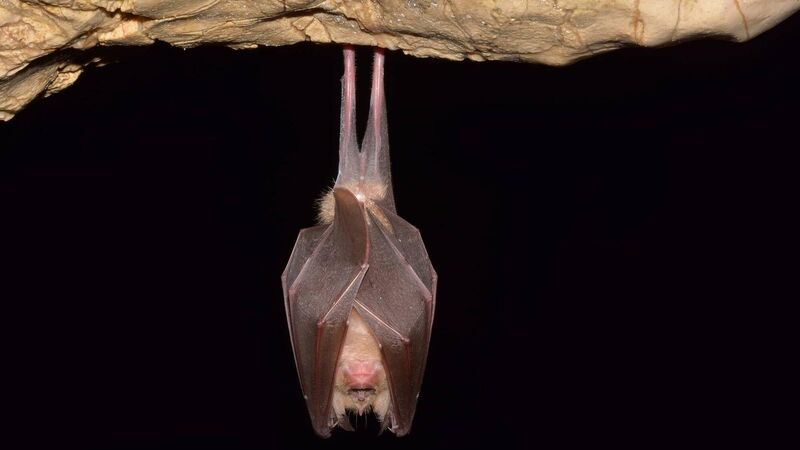

Lesser horseshoe bats depend on features like stone walls and hedgerows to guide them. Picture: iStock

In most cases, research into animal behaviour is carried out from a human view. So, what’s interesting about a new study of horseshoe bats, near the Burren, is that it sets out to see a landscape from the bat’s eye view.

Lesser horseshoe bats generally don’t fly across open areas and depend on features like stone walls and hedgerows to guide them as they move from their roosts to feeding areas and back again. Large-scale destruction of the landscape has resulted in the loss of these guiding features for bats, however.