Prime time: The real impact energy drinks have on your sleep and physical health

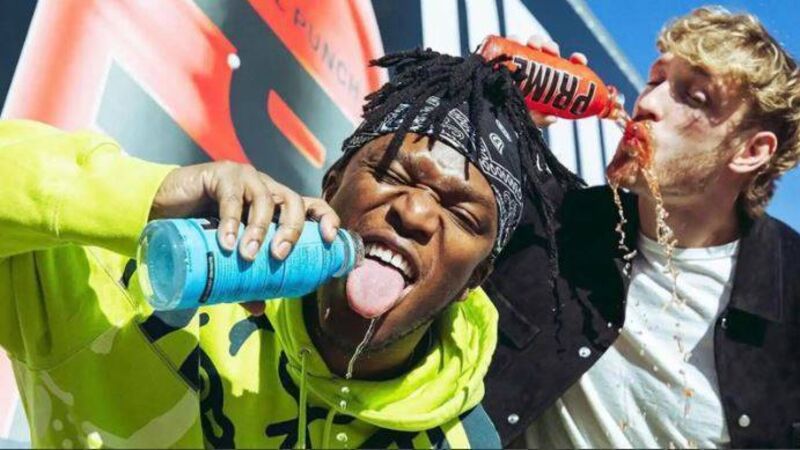

The hydration and energy drink company co-owned by UK Rapper and social media personality, KSI and US Youtuber, Logan Paul has made headlines worldwide following reports of fights breaking out among customers in a race to get their hands on the product.