Great journalist of his generation Nick Davies to give workshop in West Cork

JOURNALISTS have an aversion to being the story. Nick Davies has at least one good example. As the investigative reporter who broke the story of the phone-hacking scandal in Britain, and as the author of a book that subjected journalism to the kind of scrutiny normally applied by the media, he was used to taking the rough with the smooth. And then, not long after publishing his most recent book, Hack Attack, he googled himself one Saturday to check on his book sales.

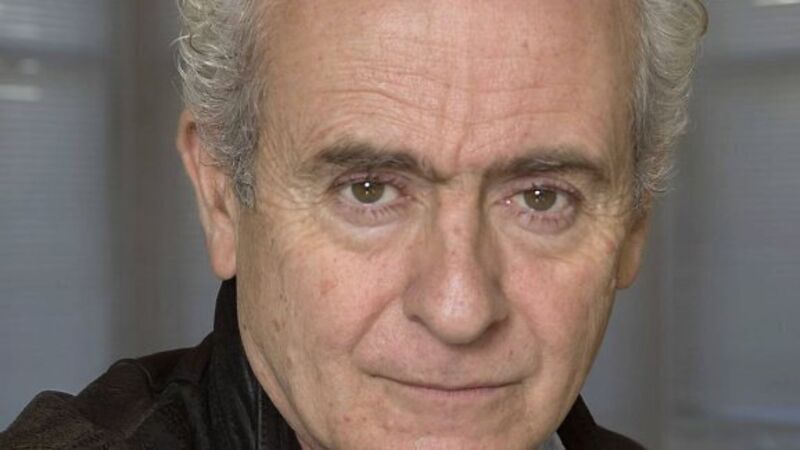

“I discovered that the Daily Mail had published 3,000 words about me in their newspaper and on their website with a big photo of me, denouncing me as an enemy of the press and a liar and a bad person,” he recalls.