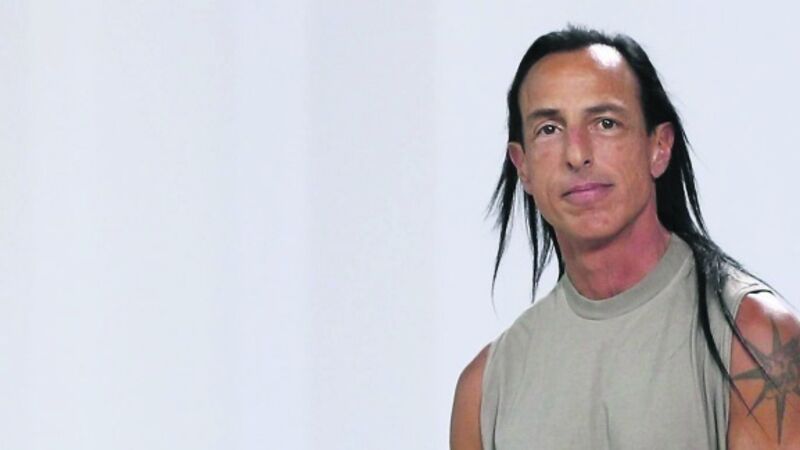

Rick Owens may be the designer of our time

You kind of want the fashion designer Rick Owens to be a monosyllabic, misanthropic recluse. It’s what the embodiment of his clothes should be, if we were going by some unwritten aesthetic script. After all, the fashion Owens presents four times a year, for men and women, on the grand Paris stage, isn’t free and easy. It isn’t simple. It often looks like rags: Precious fabrics, like cashmere, are pilled and laddered, and leather is repeatedly washed to give it the texture and appearance of a prehistoric animal’s skin. There is something monstrous about his gothic garments, with their strange, disturbing proportions attenuated and exaggerated, draped like ectoplasm clinging to thin limbs. When people wear them head to toe, as Owens’s most enthusiastic followers frequently do, they don’t look human. They look other.

“Troll clothes for the most desperate lemmings in the fashion herd,” one observer wrote in 2008 on The New York Times’s On the Runway blog. Owens appreciated the sentiment so much that he ran the phrase on his website, alongside near-universal plaudits from the rest of the fashion world.