Book review: Reflections on being German

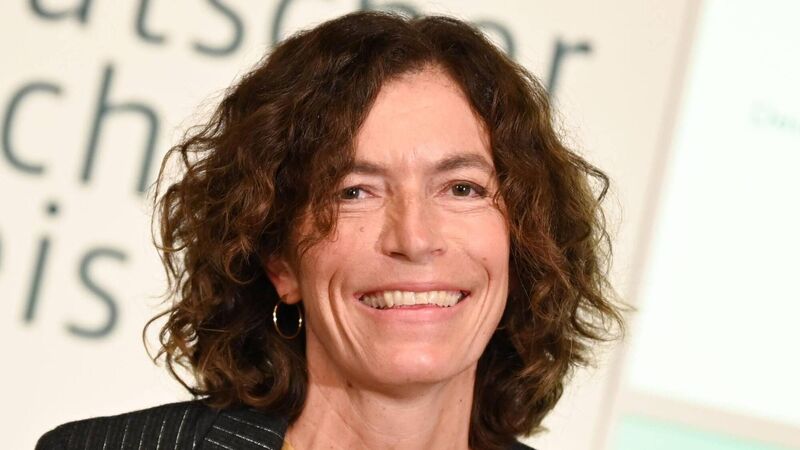

Although Anne Weber has lived in Paris since the 1980s, German history continues to cast its shadow over her. File picture: Arne Dedert/ dpa/ Pool/ AFP via Getty

- Sanderling

- Anne Weber

- Translated by Neil Blackadder

- The Indigo Press, hb £14.99

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.