Book review: The battle to birth a republic

David McCullagh shows that time and time again, the aspiration of a 32-county state was set aside for the expediency of advancing “Free State” independence.

- From Crown to Harp: How The Anglo-Irish Treaty was undone 1922-1949

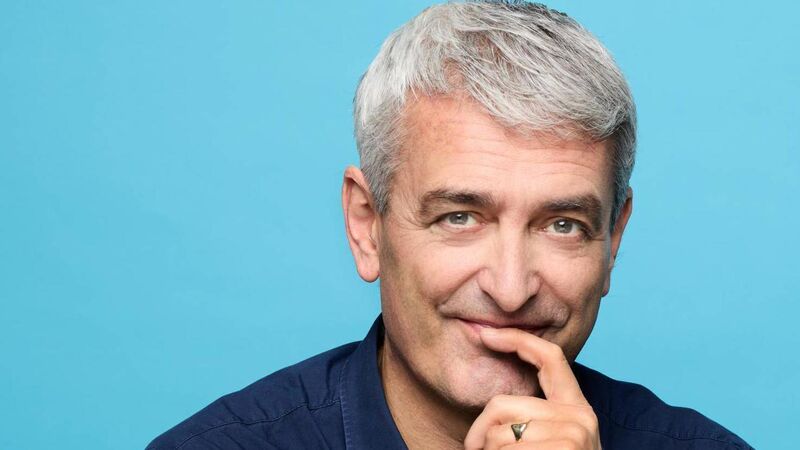

- David McCullagh

- Gill Books, €26.99

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.