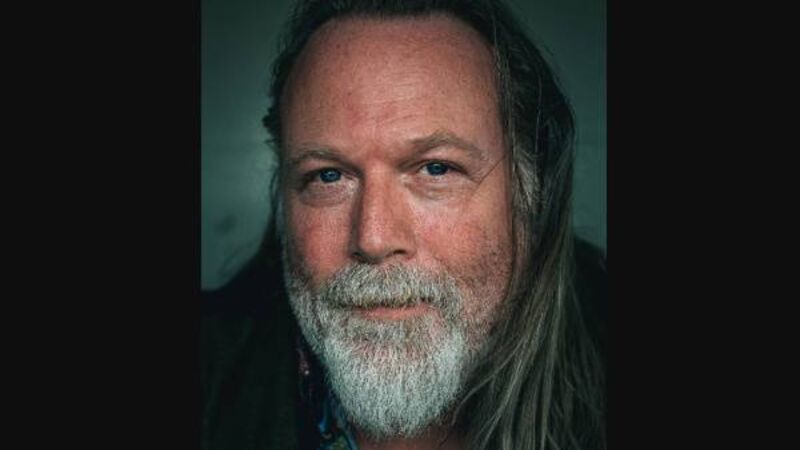

Culture That Made Me: Cork musician Joe Philpott of White Horse Guitar Club

Cork musician Joe Philpott, of the White Horse Guitar Club. Picture: Karen M Edwards

Joe Philpott, 52, grew up in Ballincollig, Cork. He co-founded Rubyhorse, an alt-rock band whose award-winning single charted in the US.

In 2012, he was a founding member of 11-man ensemble the White Horse Guitar Club.