Book review: Surviving a massacre, and the lasting emotional toll it takes

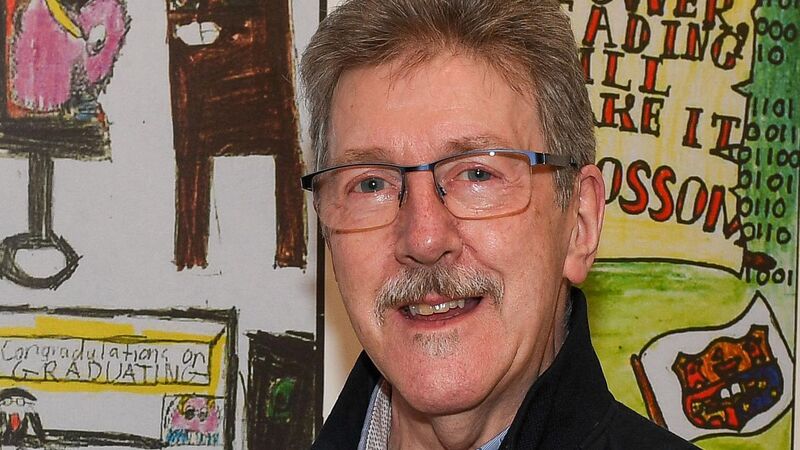

Stephen Travers of the Miami Showband, attending the launch of Punks Listen at the Boole Library in UCC in 2022. File picture: David Keane

- The Bass Player: Surviving the Miami Showband Massacre

- Stephen Travers with Alexandra Orton and fore word by Yvonne Watterson

- New Island Books, €17.95

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.