Culture That Made Me: Eimear McBride picks her favourite books, fellow-authors, and stage shows

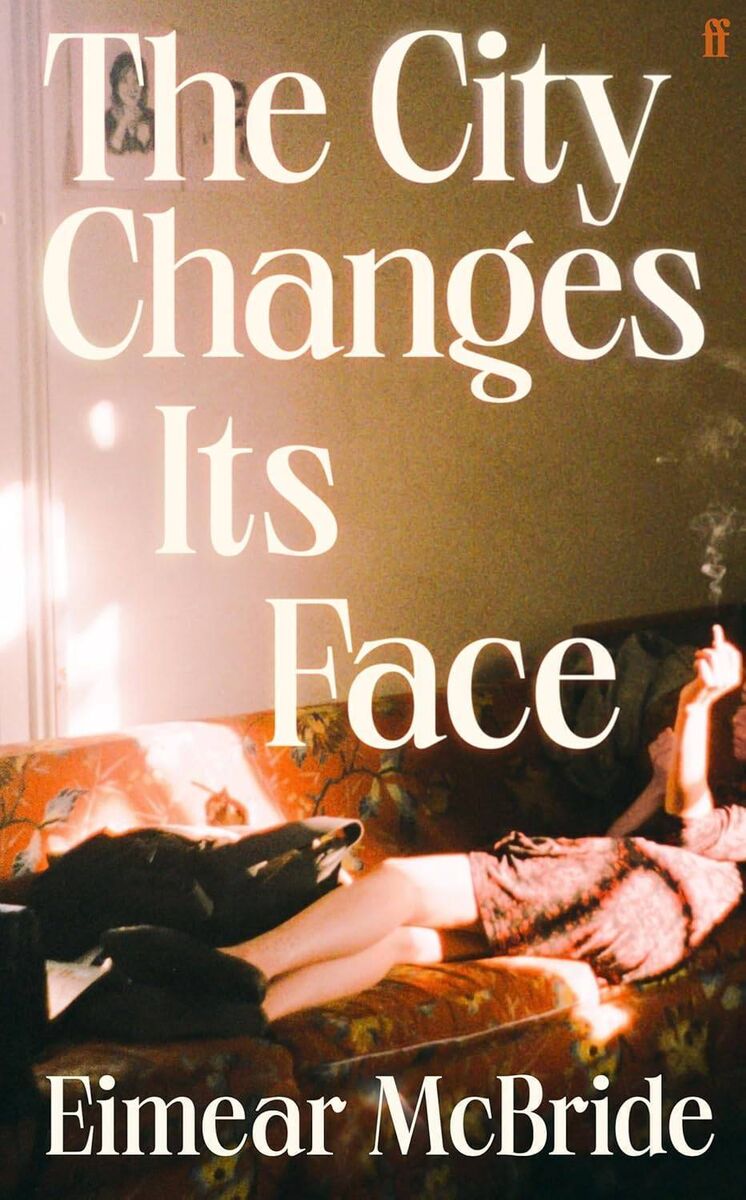

Eimear McBride recently published The City Changes Its Face.

Eimear McBride, 48, was born in Liverpool to Irish parents, but spent her childhood in Sligo and Mayo. In 2013, she published her debut novel A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing which won several Irish and international literary awards. She lived in Cork while writing her second novel, The Lesser Bohemians, which won the prestigious James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 2016. Her latest novel, The City Changes Its Face, is published by Faber & Faber.