Political notes: Opera is based on true tale of a soviet set up in an Irish asylum

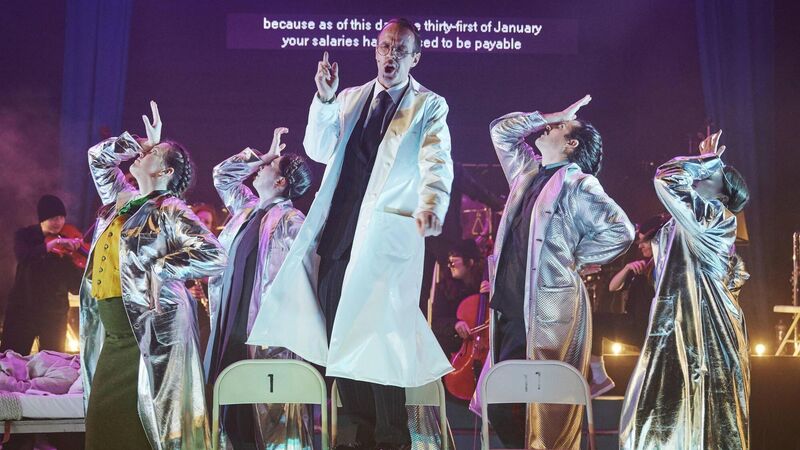

A scene from Elsewhere by Michael Gallen. Picture: Ros Kavanagh

A bold new opera by Michael Gallen entitled Elsewhere is based on the true story of the radical Monaghan Asylum Soviet of 1919. Elsewhere was performed at the Abbey in 2021 and is now on tour, directed by Tom Creed. At the centre of the narrative is a character called Celine who is fictional but is based on stories that Gallen came across in his research. Describing himself as “a politically engaged person” Gallen believes that the arts, particularly music and theatre, are a good way of communicating ideas and feelings.

A native of Monaghan, Gallen was drawn to the early decades of the twentieth century history of the Monaghan Asylum (later called St Davnets) both for personal reasons as well as for the potential drama in a tale that saw the workers and patients at the asylum raise the red flag and declare the institution the first Irish soviet. “My mother had an aunt who spent her entire life in a psychiatric hospital in the West of Ireland,” says Gallen.

The Irish soviets were a series of self-declared soviets that formed in Ireland during the revolutionary period, mainly in Munster. ‘Soviet’ in this context refers to a council of workers who control their place of work. The movement was inspired by the revolution in Russia.

The events in the Monaghan Asylum, kicking off on January 29, 1919, unfold through the visions of Celine, a patient who decades later remains ‘locked in’ to the moment of the soviet, believing herself to be its leader. Through her interactions with the charismatic ‘Inspector of Lunatics,’ fantasy and incarceration are explored.

Gallen, co-author of the libretto, written with poet Annemarie Ní Churreáin and playwright Carys D Coburn, carried out some research in a psychiatric hospital in Switzerland where the hospital director was attracted to the use of the creative arts as a means of re-socialising people following acute periods of schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. Gallen also read a book by Hanna Greally, Birds’ Nest Soup, which documents her suffering in a psychiatric hospital in the midlands in the 1940s and 1950s.

The Monaghan soviet, led by union organiser and IRA commander, Peadar O’Donnell, only lasted for a few weeks. “In the end, the workers were given all their demands including pay equity between male and female workers which was groundbreaking. But things sadly just regressed and went back to the way they had been for years.”

There was an attempt to get rid of sectarian divides in the asylum where Catholics and Protestants worked together. “At a time when sectarian tension was very much growing, they were able to look beyond all that and imagine a totally different way of living together. When the Free State came into being, there was a very strong idea of nationalism and Catholicism being linked to one another.

"A lot of the more radical leftist ideas, from the likes of Peadar O’Donnell, a socialist, began to get written out of history in the twentieth century. For the people involved in the mini revolution in Monaghan and in the fight for independence, they had a very different idea of what the country would look like, post independence.”

But as Gallen points out, the reality was a society oppressed by Church and State. “A very damning fact about Ireland was that at several points during the twentieth century, the country had the highest number of citizens per capita in the world incarcerated in psychiatric care. Poverty was a major factor. I think people really didn’t have the capacity to care for family members who weren’t neurotypical. Also, people wanted to keep those with mental illness behind doors. They were embarrassed. For a long time, the asylum system operated as a kind of net that caught all those who couldn’t function in normal society.”

Through his opera, Gallen says he is trying to reach out: “I’m trying to get at the idea of the beauty and the strength that there is in diversity and people from all sorts of backgrounds with different perspectives.”

Oriel sean nós is a feature of the opera, referring to the lilt of the border dialect. It is manifested in the hum of murmured rosaries.

“A lot of my music is drawn from the world I grew up in. I’m very interested in the rhythm of prayer that parents and grandparents would recite, whether a novena, a litany or the rosary. Their complex rhythms are built into us even though we’re not really aware of them. At several points in the opera, there is this murmuring sound,” says Gallen.

- Elsewhere is at Cork Opera House on April 17