Book review: A Brief History of Intelligence

Max Bennett takes readers back over four billion years to track the evolution of the human brain and the creation of AI.

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made our Brains

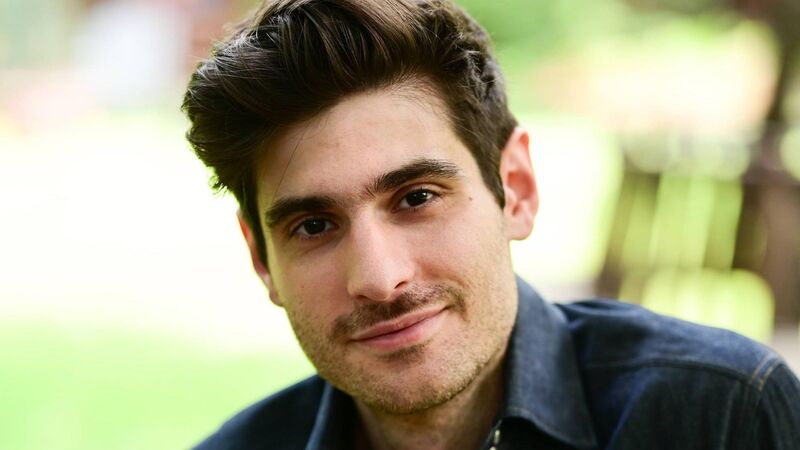

- Max Bennett

- William Collins, €17.99