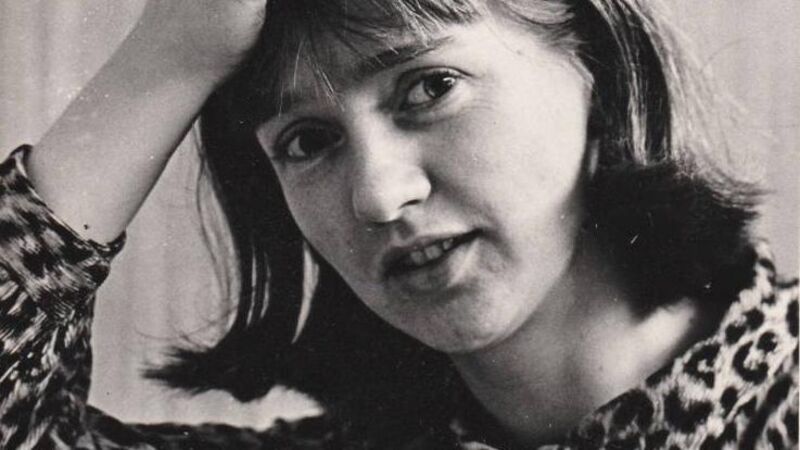

Flora Kerrigan: Rediscovering a pioneer of Cork's early film-making scene

The life and work of Flora Kerrigan will feature in Cork International Film Festvial.

The achievements of many women across all fields have been forgotten, written out of the pages of history. Joining the roll call of women whose remarkable work is now emerging from the shadows is Flora Kerrigan, who blazed a trail as a young amateur filmmaker in Cork in the 1950s and 1960s. Kerrigan’s films recently resurfaced in the course of a joint research project on women’s amateur film-making between academics in Ireland and the UK. Dr Sarah Arnold of Maynooth University describes the discovery as “pure serendipity”.

“The UK partners in our Women in Focus project had been scouring old amateur film magazines from the 1950s through to the 1970s. Each magazine had lists of names of people who would have submitted films for awards. They came across the name Flora Kerrigan for a particular film and emailed it to me. I looked up Flora and I found some mention of her in the Irish newspaper archive as a member of the Cork Cine Club,” she says.