Book Review: Stakeknife's Dirty War - tales of collaboration and sacrificing of informers

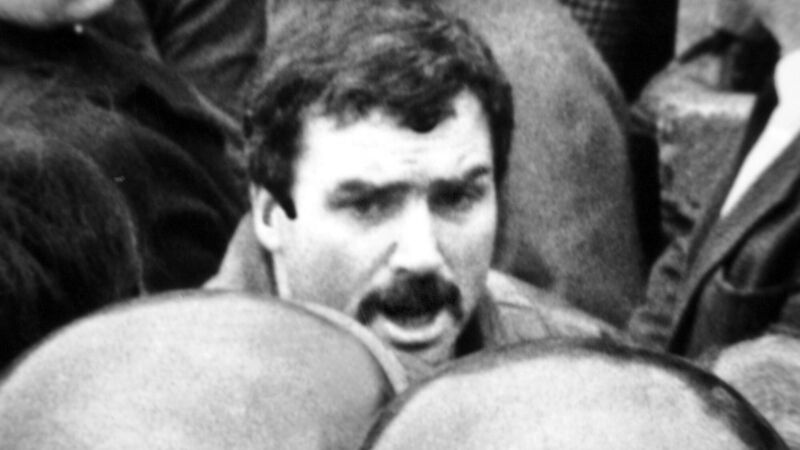

Alfredo 'Freddie' Scappaticci, codename 'Stakeknife' (circled) pictured at a republican funeral addressed by Sinn Fein's Martin McGuinness in 1987 - and later exposed as the British Army's top mole inside the IRA.

- Stakeknife’s Dirty War

- Richard O’Rawe

- Merrion Press, €17.99