Ireland In 50 Albums, No 18: Ghostown, by The Radiators (1979)

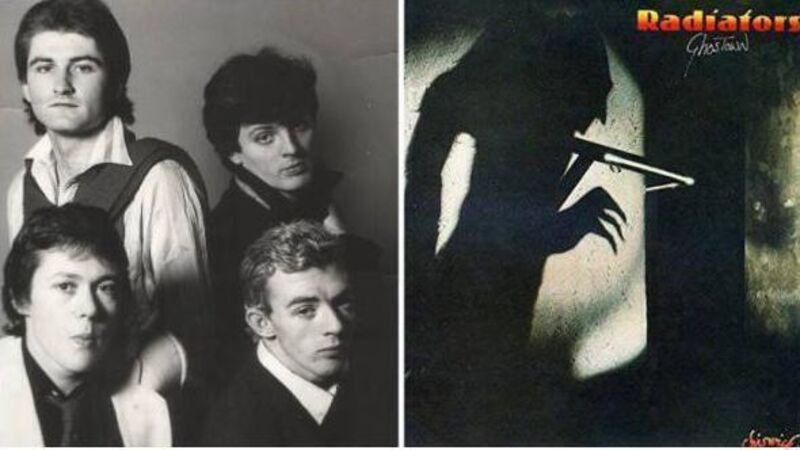

The Radiators' lineup for the Ghostown album: from top left, Mark Megaray, Pete Holidai, Philip Chevron, Jimmy Crashe.

Even by the breakneck standards of the late 1970s, Pete Holidai and Phil Chevron accomplished one of the most effective reinventions in popular music.

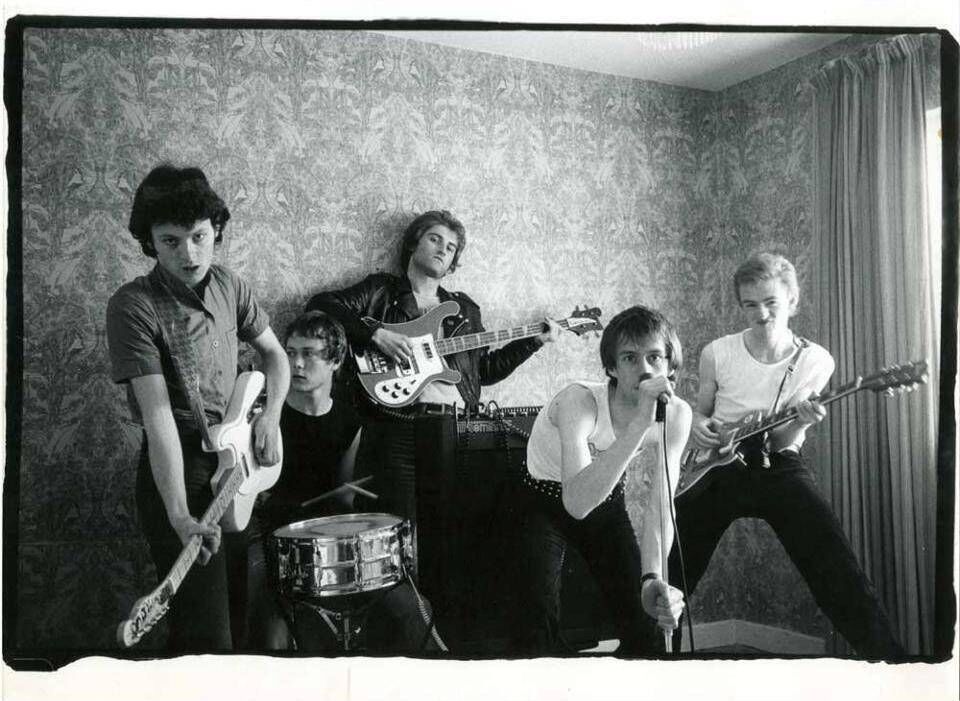

One moment, it seemed, they were the guitarists in the Radiators From Space, Dublin punks with gobby three-minute pop songs and a dynamic lead singer in the shape of Steve Rapid.

The next, having shortened their name to The Radiators, the two had moved front of stage and recorded what is arguably Ireland’s finest concept album, .

The makeover coincided with Rapid’s departure to focus on a career in graphic design that has seen him work with U2 and Depeche Mode, amongst many others.

Rapid had fronted the band on their debut album, , which, in typical punk fashion, was recorded in three days on a shoestring budget.

“Six months later, we were recording with Tony Visconti in London,” says Holidai. “It was a seismic shift.”

Visconti had worked extensively with Marc Bolan and David Bowie, and had just completed work on the latter’s albums. Understandably, he was in huge demand, and The Radiators might never have secured his services had they not toured with Thin Lizzy at the end of 1977, shortly after he’d produced their album .

“We were introduced to Tony at the party after the second gig we did with Thin Lizzy at the Hammersmith Odeon,” says Holidai. “We were going back to Ireland for Christmas, and Tony said, if we’re going to work together, I need you to write a couple of hits and send them over to me.

"So I wrote and Phil wrote , and we recorded a demo of them both in the shed at my parents’ house in Robertstown, Co Kildare.

“We went on to record both those songs with Tony around February 1978. We were very happy with the work and the relationship, and after that we started writing in earnest. I think it helped that we were in London at that point, rather than in Dublin, because it gave us a different perspective.

"When James Joyce wrote , it helped that he was in exile. I’ve never made the comparison with , but others have. We felt we were in exile too.”

Recording began at Good Earth Studios on Shaftesbury Avenue in London in the summer of 1978.

When Holidai remixed the album for a re-issue 40 years later, he got to listen back to individual tracks on recordings such as , and he was reminded of just how inventive Visconti had been in the studio.

“I remembered how Tony had asked that I play banjo on the chorus,” he says. “Now, I didn’t have a banjo and had never played one. But Tony took my Stratocaster and taped up the two lower strings.

"Then he put a snare drum between the speaker and the microphone, and gave it a bit of EQ, and he constructed the banjo sounds out of that.”

As the album evolved, all the band had a hand in writing songs. Drummer Jimmy Crashe contributed to the final version of , and he and bassist Mark Megaray contributed to the album’s closer, . Holidai and Chevron were the main writers, however.

was not the first Irish concept album, Horslips having by then released both and .

But this was something else entirely, a highly literate folk/rock/cabaret concoction that elevated the romance and squalor of their native city to the level of high art. Comparisons to Joyce were actually warranted: think Dubliners, with guitars.

When Visconti had finished mixing the album, a playback was arranged at Good Earth for a number of Irish and UK music journalists.

“We played them all the tracks,” says Holidai, “and when it was finished, there was complete silence. They seemed to be astonished.”

Had the album been released as scheduled, the broader reaction might also have been one of astonishment. So what happened?

“That’s a hard one,” says Holidai. “All I can vaguely say is that Chiswick may not have had the funds to cover the budget for the recording. So there were a couple of individuals who came on board, saying they’d cover the cost, and it was because of them that the record went ahead.

"But these individuals were also present at the playback. And literally, within two days, they reneged on the agreement, which left us with an album that couldn’t be paid for.

“It would be another year before Chiswick licensed ’ single . They had a top ten hit in America with that, and they finally had the funds to get out there.”

Among the album’s first wave of fans was Dr Michael Murphy, who now lectures on entrepreneurship and arts management at the Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Dun Laoghaire, and is the author of the recently published book, .

“I bought a copy the week it came out,” he says. “I was a teenager, and still at school. But these fellows weren’t much older than me, and they were making stuff that felt like a very sophisticated statement, telling someone like me that Ireland’s cultural past wasn’t the minefield we thought it was. It’s no exaggeration to say that blew my mind.”

Sadly, The Radiators’ moment had passed. The media took little interest, sales were poor, and the band split up a short time later.

They mostly continued in music: Chevron became a Pogue, contributing to their classic album, ; Holidai joined Light A Big Fire; and Megaray performed with the Eric Bell Band and Auto Da Fé.

Despite the lack of commercial success, became a word-of-mouth cult classic. In 1987, the Radiators reformed for an Aids benefit concert in Dublin, and Chevron debuted a new song, .

It was what Murphy calls “the first openly gay Irish pop song. That was era-defining. It was incredibly brave to perform a song like that in the ’80s.”

The track was released as a single, and added to a reissue of in 1989, along with another new Chevron number called .

In 2003, Holidai and Chevron reunited with Rapid as the Radiators (Plan 9), with former Pogue Cáit O’Riordan playing bass for a spell.

They released their third studio album, , in 2006, by which time they had reverted to their original name, the Radiators from Space.

A collection of covers, , was the band’s final release before Chevron succumbed to cancer of the throat, passing away in 2013. Megaray died in 2016.

Holidai oversaw the bells-and-whistles double-album re-issue of in 2019, the original album being augmented with demo takes and live recordings.

“Chiswick sent me over the multi-tracks on four reels of tape, and I was able to fabricate some work-in-progress mixes,” he says.

“Listening to those tracks again, I was transported back to Good Earth Studios in 1978. I think it’s a testament to the record itself, the fact that was considered worthy of a 40th-anniversary reissue.”

Murphy contributed the sleeve notes, outlining the album’s importance in the history of Irish music.

“ is the most ambitious album ever made by an Irish artist,” he says now. “I still listen to it obsessively, and I still don’t understand it completely. But it’s a cultural capsule, and utterly timeless.”

- Further information: theradiators.irish