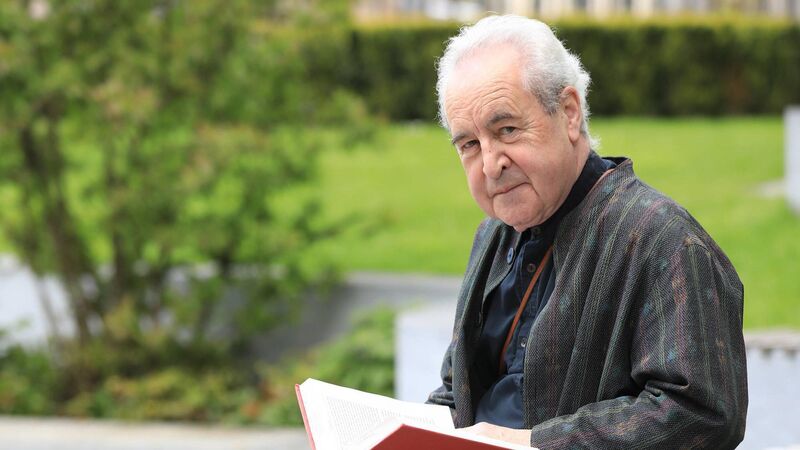

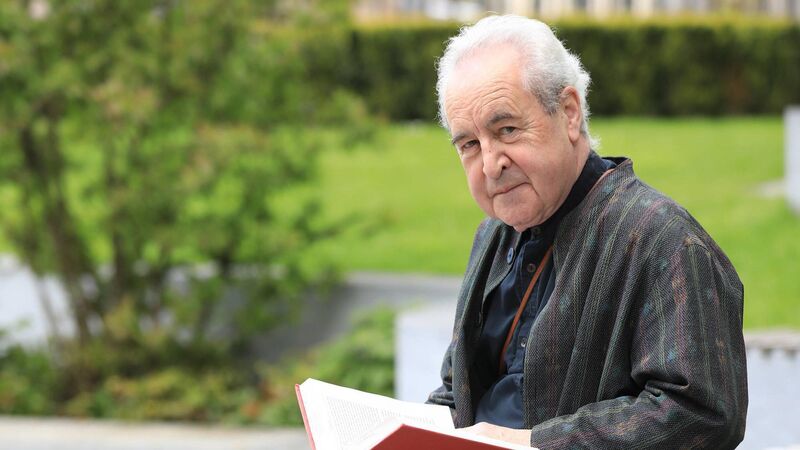

Book Interview: John Banville on new novel 'The Lock-Up' and maintaining a high standard

John Banville.

- The Lock-Up

- John Banville

- faber, €14.99; Kindle, €8.28

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

John Banville.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

Newsletter

Music, film art, culture, books and more from Munster and beyond.......curated weekly by the Irish Examiner Arts Editor.

Newsletter

Music, film art, culture, books and more from Munster and beyond.......curated weekly by the Irish Examiner Arts Editor.

© Examiner Echo Group Limited