Barbara Walker at the Glucksman, UCC: Addressing racism through art

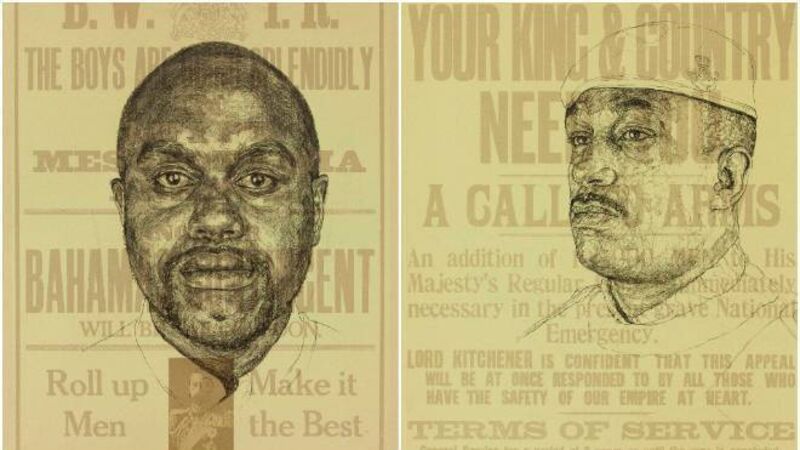

Images from the Glucksman exhibition featuring Barbara Walker.

The British artist Barbara Walker has the distinction of using the humblest of materials to investigate issues of race and privilege. Awarded an MBE in 2019 for services to British Art, she often works in pencil or conte crayon, drawing on paper or directly onto the gallery walls.

As demonstrated in The Big Secret III - one of her contributions to A Line Around an Idea, the current group exhibition of drawings at the Glucksman Gallery in Cork - it is not unusual for Walker’s artworks to feature a blank space where there might be a human figure. Such absences reflect what she perceives as the erasure of black participants from official accounts of the two world wars and other historical events.