Joseph O’Connor on his novel My Father’s House and the brave Munster man who inspired it

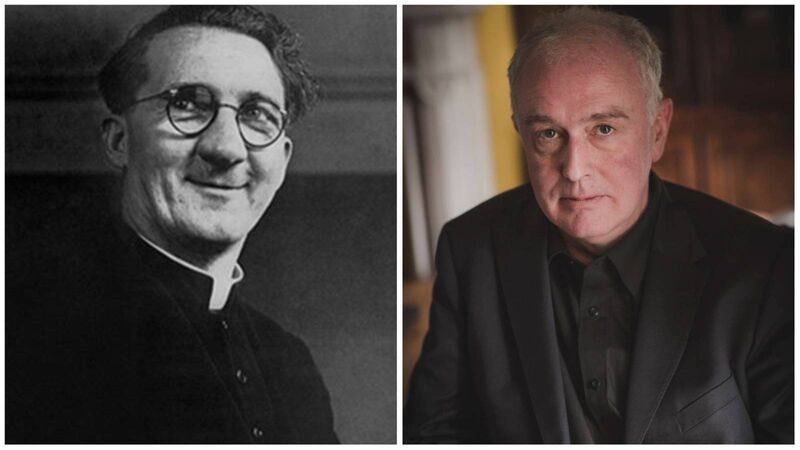

Hugh O'Flaherty is the subject of Joseph O'Connor's latest novel, My Father's House

I can’t remember the first time I heard the story of Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty (1898 - 1963), but I think it might have been in Listowel. I’ve been attending the world famous Writers’ Week on and off for 30 years, since my very first efforts at writing. At some point, late one night, someone told me about Hugh O’Flaherty and the Escape Line he organised and led in Rome during the Second World War. Over the years, I researched and read more about him. I was always more amazed by his legacy.

Hugh O’Flaherty’s heroism is both gripping and inspiring. It always had the makings of a tense psychological thriller, and that’s what I hope I’ve written. A novel in the same vein of my Star of the Sea. But there are other nuances and meanings to his story.