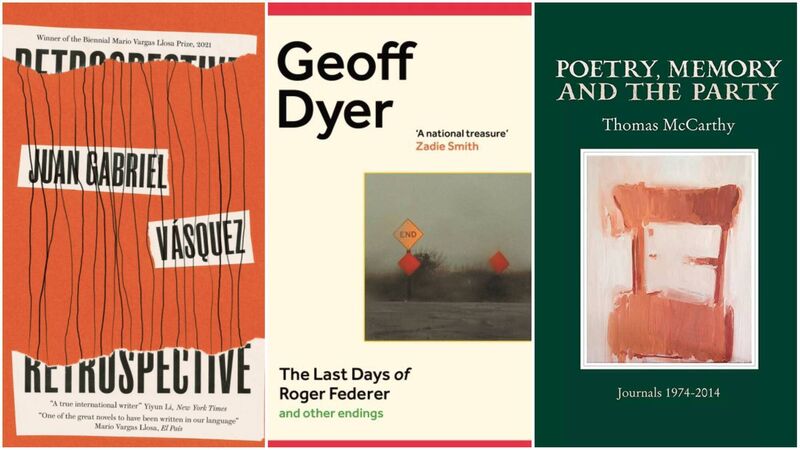

Cork writer Alannah Hopkin selects her favourite books of 2022

Alannah Hopkin's favourite books of 2022

I like a book that stops me in my tracks and demands to be read before normal life can resume.

All three of my books of the year share this quality.

- Poetry, Memory and the Party - Journals 1974-2014

- Thomas McCarthy

- Gallery Press, €17.50

Poet Thomas McCarthy’s long-awaited memoirs, a substantial volume of 456 pages, was published in January, 2022, and did not disappoint.

In January 1974, McCarthy was a 19-year-old student and part-time gardener, already a published poet, house-sitting at Glenshelane House, the Cappoquin home of his friend and benefactor, Brigadier Denis H Fitzgerald, grandson of the Duke of Leinster.

This Anglo-Irish world is in total contrast to the poverty of his own family background, his parents both ailing, and both dead by 1979. He describes Ireland 1974 as being in the grip of “this heavy, Republican anarchy”.

The ‘Party’ of the title is Fianna Fáil, and his life-long allegiance to it is something that many admirers of his poetry find hard to understand. He refers to his loyalty to Fianna Fáil as “the self-destruct button of my poetic ‘career’”.

Career is in inverted commas as he has recently questioned Seamus Heaney’s use of the term for a poet’s progress through life, a new way of thinking back then.

By the end of the book, in December 2014, McCarthy is recently retired from his other, more conventional career as a librarian in Cork city, the happily married father of two grown-up children, a member of Aosdána since 1995 and a well-liked and respected figure in the Irish literary world and beyond.

He worries about his former mentor, John Montague, in his impecunious old age; “Don’t expect writing to give you a living, but its inability to give you a living is not a judgement upon its importance,” he advises his children.

He marvels at the great shift in Irish poetry since the death of Yeats caused by the arrival of the female voice at the centre of Irish literary life: “I have written the longest and deepest essays on women, from Molly Keane to Eavan Boland to Paula Meehan. Critically I’ve written almost nothing else of importance.”

One of the great pleasures of reading memoirs is the gossip, and McCarthy knows this.

But he is also kind and tactful and aware of the wider implications of the stories he might tell after 40 years of activity in Irish literary circles.

As a near contemporary of Tom’s, active in some of the same circles, I was pleasantly surprised by his benevolence, and his lack of grudges.

I had never suspected that there was a rivalry between Tom and his Cork city neighbour and fellow Waterford-born poet, Seán Dunne, books editor of this paper, who died tragically young in 1995.

Both were proteges of John Montague, who was not above fermenting the rivalry.

Later on, during his stressful years working in Cork 2005’s Capital of Culture offices, a rollercoaster ride of elation and depression, he became famous for resigning — or threatening to — more often than anyone else on the team.

One reason that the memoir is such compulsive reading is that it is brilliantly edited, somehow managing to present a cast of thousands, without footnotes.

For this McCarthy thanks Peter Fallon, the publisher of the Gallery Press, and his assistants Jean and Suella.

McCarthy is excellent on Molly Keane, a friend of the Brigadier, charting with a beady eye her transformation from witty socialite to literary lioness for the second time in her life when her novel Good Behaviour is short-listed for the Booker Prize. He ends his thoughtful, wide-ranging memoir with her words: :To write is hell, but not to write is even worse.”

- The Last Days of Roger Federer and Other Endings

- Geoff Dyer

- Canongate, £20

Anyone with even a slight acquaintance with the work of novelist and critic Geoff Dyer will know at once that The Last Days of Roger Federer and Other Endings is not going to be about tennis.

Dyer is an eternal enfant terrible, a professional contrarian who has written extensively about recreational drugs, raves and the Burning Man festival, as well as art, photography and literature.

He is also obsessed with tennis. His latest book, however, while a bit light on Roger (always Roger, never Federer), is very much about endings — how people’s work changes towards the end of their lives, be they writers, musicians, artists or indeed, tennis players.

Roger does get several mentions, but just as Dyer’s book about DH Lawrence, Out of Sheer Rage, was about not writing a book about DH Lawrence, this book is more about being Geoff Dyer than being Roger.

Dyer was a protégé of the writer and critic John Berger (author of the seminal text Ways of Seeing), and I first came across him as the editor of Berger’s collected essays.

He is extremely well-read, but often reluctant to take himself seriously.

But he is surprised and somewhat alarmed to find himself already in his early 60s, and ever-more preoccupied with the passing of time and the afflictions that come with age.

He has already had a stroke, and his lifelong addiction to tennis has left him with “multiple permutations of trouble: rotator cuff, hip flexor, wrist, cricked neck, lower back, and bad knees (both)”.

While his obsession with tennis has not diminished, marriage and a move to Venice, California, (“beside the microplastic-threatened ocean”) have perhaps taken some of the bad-tempered edge off his work.

But ironically this collection of themed meditations on “things coming to an end, artists’ last works, time running out” is far funnier, as in laugh out loud funny, than anything else of his I’ve read.

His reading at this year’s West Cork Literary Festival was funnier than most comedians.

I loved his piece on poetry readings, which begins: “At any poetry reading, however enjoyable, the words we most look forward to hearing are always the same: ‘I’ll read two more poems.’ (The words we truly long for are ‘I’ll read one more poem’ but two seems to be the conventionally agreed minimum’)”.

He is of course unusually well-read in poetry as well as philosophy, but, as he puts it elsewhere: “A sense of humour is about so much more than being funny.”

Dyer’s method could be described as accumulated riffs on whatever theme is at hand — whether the concerts of the octogenarian Bob Dylan, the later novels of Martin Amis, the late thoughts of Nietzsche, JMW Turner’s bleached-out late landscapes or Beethoven’s passionate late quartets.

Just as no topic is too highbrow, none is too mundane, for example, his description of accumulating free hotel shampoos on such a massive scale that he will never need to buy it again.

While Zadie Smith refers to him as “a national treasure” some critics have accused him of avoiding the bigger questions in favour of lightweight cultural commentary, resulting in work that is “more wide than deep”, according to Terry Eagleton. But even “wide work” can be stimulating, and if it makes you laugh as well, why complain?

- Retrospective

- Juan Gabriel Vásquez

- Maclehose Press, £20

Colombian Juan Gabriel Vásquez’s new novel, Retrospective is a compelling page-turner, a family saga that stretches from the Spanish Civil War to 1950s suburban Bogotá, China’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, Colombia’s rural guerrilla movement, and contemporary Barcelona.

Vásquez has quite a following in Ireland, since his novel The Sound of Things Falling won the 2014 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award.

The main character in Retrospective is the film director, Sergio Cabrera, born in 1950, who is in Barcelona in 2016 for a retrospective of his films, accompanied by his 18-year-old son, Raúl, whom he does not know very well.

It is a difficult time for Cabrera, who is coming out of a prolonged depression.

His father has just died, his marriage to a younger woman is falling apart, and she has gone back to Lisbon with their three-year-old daughter.

He has recently returned from Bogotá, where he went to vote for a peace agreement that could end 50 years of armed struggle, but the majority rejected it.

In the intervals between the showing of his films, he reveals the full story of his family’s political allegiances and struggles to his son.

The fact that Sergio Cabrera is a real person is clearly spelled out in the book’s blurb, though Colombian readers would be aware of the renowned film director and his family. Cabrera’s father, Fausto, was an exile from Franco’s Spain who became an actor and married a younger woman from a well-known Colombian family, Luz Elena Cardenas, who also acted.

When Sergio and his sister, Marianella were in their early teens, their parents accepted an offer from Maoist China to take lucrative but clandestine posts as Spanish teachers.

Friends and relations in Bogotá were told they were in Europe, and letters redirected to confirm that impression.

After returning to Colombia from China, Sergio, his father, his mother and Marianella were all politically active, and only narrowly escaped from the guerrilla warfare of the late 1960s with their lives.

Sergio and Marianella spent three years living and working among the rural poor, having trained in guerrilla warfare in China.

It is an extraordinary story by any standard. What novelist could resist?

Events are vividly recounted in Vásquez’s fast-moving prose, seamlessly translated by Canadian Anne McClean.

It is easy to see why Cabrera’s life story attracted Vásquez, 23 years his junior, whose other works have explored crucial events in Colombia’s violent history.

How could he resist a true story that gave the inside track on the revolutionary struggle that was intended to liberate the proletariat from economic and political oppression?

I had never understood how the Maoist version of communism was the dominant ideology in Latin America, but now, after a beautifully crafted and exhilarating read, I understand how that came about.

The novel has been rapturously received in the Spanish-speaking world, winning the Biennial Mario Vargas Llosa Prize in 2021, and just recently the prestigious French award for Best Foreign-language Novel of 2022.

Vargas Llosa himself in El País declared it “one of the great novels to have been written in our language”.

Inevitably, people have complained that because it tells a true story, it should not have been published as a novel, but as a biography.

But it displays the craft and architecture of a novel: whether it is true or not is irrelevant.

Vásquez comments in an Afterword: “My work consisted of giving those episodes an order that went beyond a biographical recounting, an order capable of suggesting or revealing meanings not visible in a simple inventory of events …. Interpretation is also part of the art of fiction: whether the person in question is real or invented is, in practice, an inconsequential and superfluous distinction.”

The latest news is that Sergio Cabrera has been appointed Colombia’s ambassador to China.

Perhaps there is another novel waiting to be written.