'He thought like a jazz musician': Iain Ballamy to play tribute to Matthew Sweeney

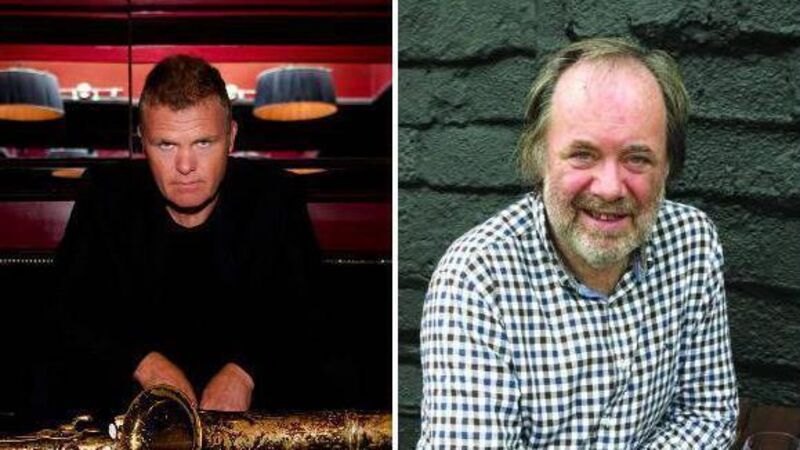

Left, Iain Bellamy; right, the late Matthew Sweeney.

English saxophonist Iain Ballamy first met late Irish poet Matthew Sweeney at the end of the 1990s, during the making of a jazz television series filmed in Southampton. The pair had a passionate and mutual love of jazz, yet the connection between them seemed more powerful, immediate and unspoken.

“I think by the way I played, and by the way he wrote, we just knew that we liked each other,” says Ballamy. “We could relate. We clicked.”