Book interview: Family values brought to book by Wimpy Dad

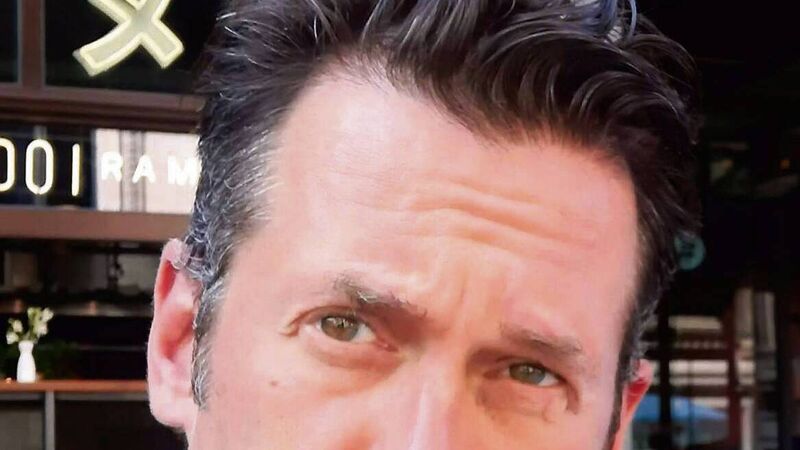

Author Dave Diebold David Diebold Diary of a Wimpy Dad

- Diary of a Wimpy Dad

- Dave Diebold

- Monument Media: €11.95. Kindle: €4.18

Shortly before Ireland’s first lockdown in March 2020, Molly, the Diebold family dog, was unable to get up. At 17, it was clear that her life was nearing the end. Knowing how much the dog meant to their children, David and Emily gathered the family together to ease their beloved pet’s passing.

“Our eldest son, Zacchary, flew home from Brussels,” David tells me, over Zoom from his home in Skerries, Co Dublin. “Everyone wanted to spend time with the dog. Every one of them took turns curling up in the dog’s basket at night so she wouldn’t be alone. It was heartbreaking. We all went with her to the vet on the day and put our hands on her chest until her breathing stopped. It was a profound and bonding experience.”

Zacchary was still at home when lockdown happened, but, working in IT, was fortunately able to do all his work on his laptop. A true family man, David was delighted to have everyone at home.

“The sun was blazing,” he says. “We ate outside every night, only moving in when the weather turned weird. We played board games every night and binge-watched movies. It was like Christmas in the sun.”

Those weeks reminded David of the days some years before, when, leaving his full-time job as features editor of the Evening Herald, he became a stay-at-home dad. As he was adjusting to his new role, he penned a weekly column for The Herald, relating the minutiae of the experience. He wrote the column for four years but has now edited and condensed them down to a year for a book titled Diary of a Wimpy Dad. And he dedicates it to the aforementioned Molly. ‘Queen of Farts.’

“At the time, being at home living with the family was still fresh for me,” says David. “There was almost a mindfulness vibe in writing the column. I was ultra-receptive to the banal detail of every single day, having missed out for such a long time.”

He describes his family back then as three hairy, monosyllabic teenage boys and a pathologically cheerful, explosively hormonal pre-teen girl, but in these humorous slices of life, he comes down hardest on himself, painting himself as an inept role model who almost always gets things wrong.

Some of the chapters are poignant to the point of tears. When his ‘mom’ is dying in the States, and he has to say goodbye to her over the phone, he can’t quite find the right words.

“I wrote that blow by blow as it happened. In retrospect, it was quite funny talking all this nonsense, and thinking, ‘surely this can’t be the last phone call’.”

It’s abundantly clear that David adores his family — and loves the chaos that large families bring.

“I really like a busy house; a loud house with slamming doors and laughing,” he says, telling me how much he misses his children, now that they have all returned to their jobs or to college. However, he’s not a fan of housework.

“Neither Emily nor I have any interest in domestic chores,” he says. “We are terrible. The description I write of a house full of cobwebs with the garden trying to break in is entirely accurate.

"We have other interests. There are too many books to read and too much wine to drink.”

Emily doesn’t like cooking either, but David revels in it — and has become the family chef.

“My cooking started as an apology,” he says. “When I was features editor, I would get home late. My day started at 4.30am, when I got up to take a taxi to the office, and after work, I’d feel obliged to meet the editor or a colleague who wanted to meet in the pub. I’d get home at seven, but there would be phone calls at eleven at night. It would be: ‘Did you see that thing on Vincent Browne? Call the studio now and get your man to write 500 words for the morning. Or don’t bother showing up.

“By the time I got home, Emily would have fed the kids. I would make her something really nice that I would have picked up, just for us. I was making up for lost time, making a meal really count. Once I was working from home, I was able to continue the apology full-time.”

This love for a united family most likely stems from David’s rackety childhood. The couple he describes as mum and dad are actually his grandparents. They brought him up, because his real mum — his sister — was emotionally unable to do so. He has since met his real dad — now deceased — and gets on well with his half-brother.

Life at home for David isn’t always ideal. The third lockdown was as gloomy as the first was joyful.

“Winter was interminable,” he says. “I was crossing off the days as if I was in gaol. Sammy, our third son, in his third year at Trinity, moved out to a house in Ranelagh to be with his mates. He’s the most culinary curious and really appreciates his food. The dinner table is not the same without him.”

When David left the Evening Herald, he and Emily set up a local newspaper; this along with their publishing company, Monument Media has kept them busy.

“The paper is still going — we haven’t missed an issue, but with virtually no advertising we had to downsize from 40 to 28 pages. We had to go on PUP because there wasn’t enough coming in to pay ourselves and meet our overheads. And with nowhere to go, nothing to do, and only feeding four of us, life was hard. But the worst thing was that winter is the time we usually plan the rest of the year; where to go, who to see, and which city to visit abroad.

“And we worried about Emily’s parents. Her mother has dementia and her father cares for her. They normally came out once a week, and I’d cook lunch and dinner for them, but they could not, and Emily was aware of how much was on her dad’s plate.”

David walked away from a great career in journalism, writing for most of Ireland’s national newspapers, winning Feature Writer of the Year in 2011. He worked for the Evening Herald for 12 years, his role constantly evolving. Starting as a freelance writer, he moved into sub-editing before being made editor of their Friday magazine. And from there, he got the aforementioned features editor gig.

Would he ever consider returning to a day job?

“Never. I don’t think I’m suited to it — I’m too sensitive. When I’m working for someone else, I’m subject to their whims and their moods.

"If someone treats me badly because they are having a bad day, it’s a trigger for me. It’s, ‘I’m out of here. I don’t have to deal with you’. If you work as hard for yourself and your family as you did for someone else, you will always get by. If it came down to it, I wouldn’t work for a paper or a business, but I’d have no problem stacking supermarket shelves at night. I wouldn’t have to talk to anybody.”

What did it feel like revisiting the columns a few years on? “I was reluctant at first,” he says, “but the more I read back over them, the more I got inspired to finish the book. It was revisiting those moments and reliving them.

“There was much more warmth in them than I’d remembered. And I realised that ultimately, the columns are love letters to my family.”