B-Side the Leeside - FIFA Records: 'Why can't we have a label out of Cork?'

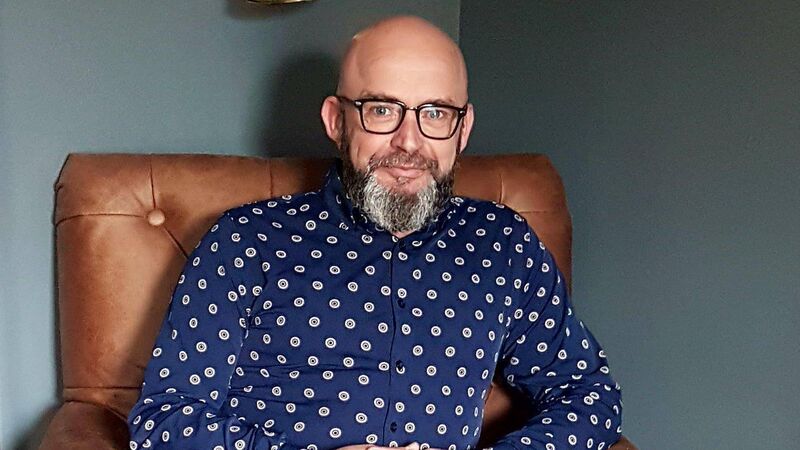

Eddie Kiely of Fifa Records in Cork.

Cork-based indie label FIFA Records has had a long and strange journey since its inception in the early Noughties. Emerging as the old music-business model was on its last legs, and functioning throughout the long feeling-out process that led to streaming, the rise of Bandcamp and the return of vinyl, the label now finds itself in something of a purple patch, with a fresh crop of new releases.

It all started, says label A&R and artist manager Eddie Kiely, with a conversation held by the label’s co-founders, among them Ashley Keating of the Frank and Walters, at the time in search for an outlet for the band’s new music.