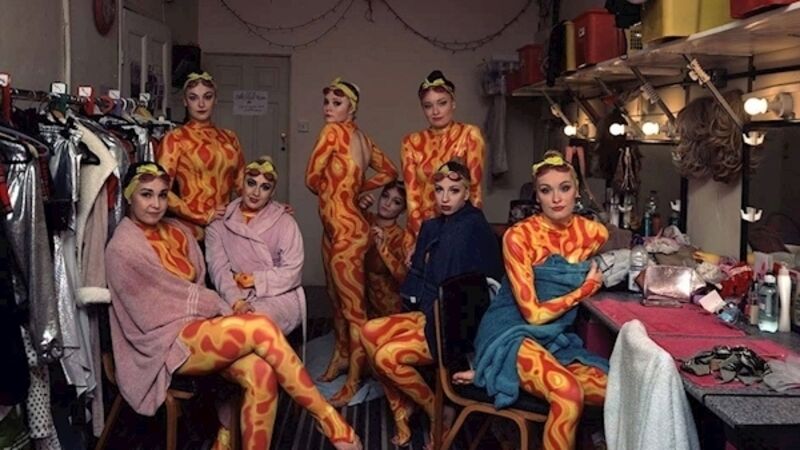

Behind the scenes at the Big Top

In advance of his exhibition in Cork, Peter Lavery tells about his 50 years photographing circus performers

It's 250 years since retired sergeant-major Philip Astley formed Ha’penny Hatch Riding School in London in 1768, founding the art form we now call circus and instituting the role of ringmaster to boot.