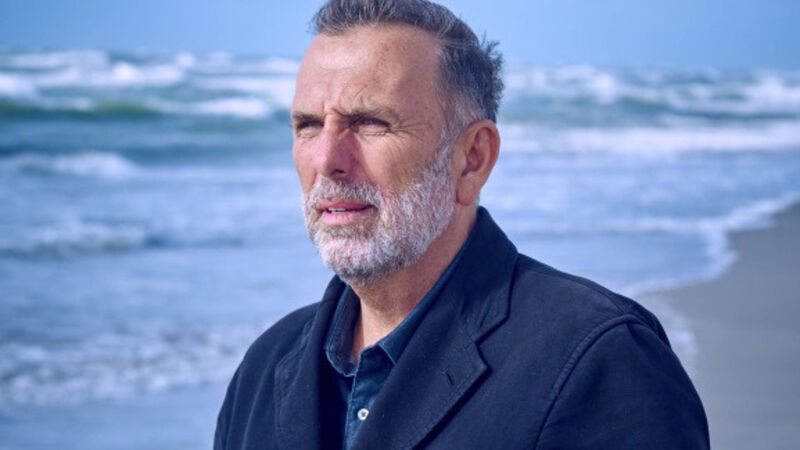

Writer Allan Jenkins reaps the benefits of being an early riser

YOU can’t say Allan Jenkins doesn’t practise what he preaches. It’s 10.30am when I ring him to talk about his new book, Morning — How to Make Time: A Manifesto, which examines the many benefits of rising in the early hours. I’m on my second coffee of the day and eager for insights on how I can transform myself from a night owl into a lark. When I ask him what time he got up at, he laughs.