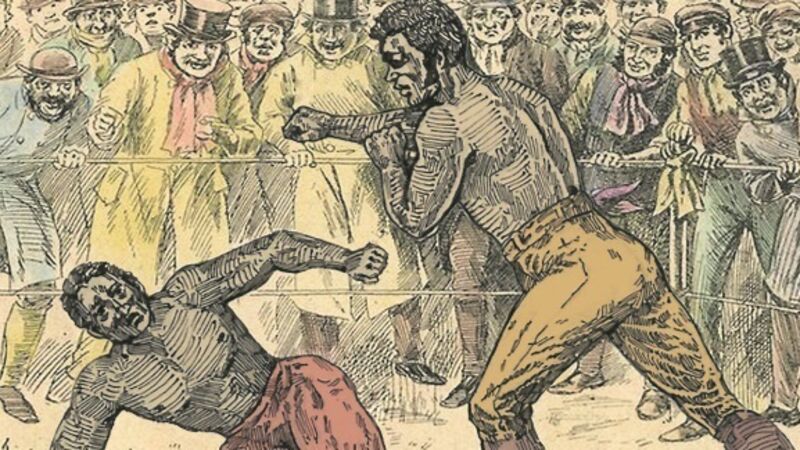

Tom Molineaux: The slave who boxed his way to freedom before dying destitute in Ireland

IN the grassy, hilltop graveyard in Mervue, close to Galway City, lie the remains of America’s first boxing star. His name was Tom Molineaux. He was buried there in 1818. His story is remarkable.

“There were just a few people who knew about him, really,” says Des Kilbane, co-director of Crossing the Black Atlantic, a documentary about the life of Molineaux. “Even in Virginia, where Molineaux grew up, when we were over there filming, only one historian heard about him. That was about it. More people knew about him in Galway than in Virginia.”