Writers looking to the past to improve modern Irish literature

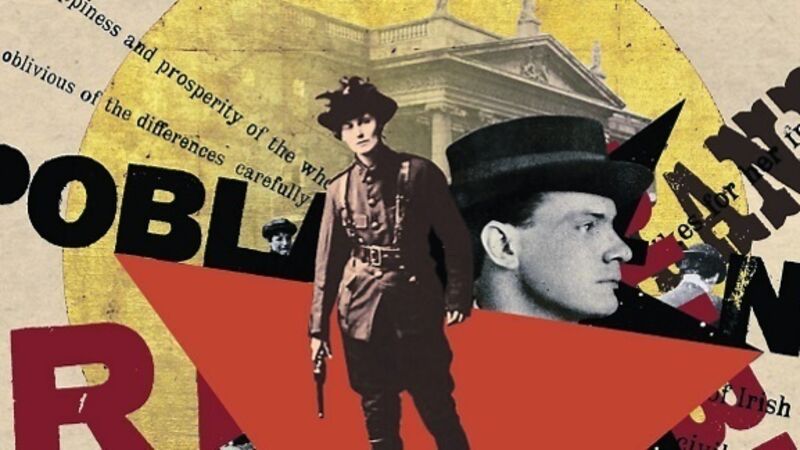

THE future of Irish literature has never looked brighter but now some of the country’s finest writing talent are looking to the past, assembling to add their voices to the chorus of commemoration for the Easter Rising.

Literary journal The Stinging Fly, which has nurtured and promoted Irish writing since 1997, has released a bumper spring issue titled ‘In the Wake of the Rising’, guest-edited by writer Seán O’Reilly.

He says the special issue is intended as an alternative space for writers to re-read and respond to the events of 1916, its background and legacy, and to the Proclamation itself. The results are absorbing and eclectic, featuring contributions from established writers such as Kevin Barry, Patrick McCabe, and Evelyn Conlon, and emerging talent including Lisa McInerney, Kevin Curran, and Doireann Ní Ghríofa.

O’Reilly initially discussed the idea of a special Rising edition with The Stinging Fly publisher Declan Meade and they decided to invite submissions.

“We were wondering what kind of response we’d get. But there was just a belief in the idea that this was a good thing to do, that writers should be engaging more. A lot has been written, particularly in America, about a crisis in fiction itself, whether contemporary fiction can represent reality any more — if it needs to move to other ways of representing reality like collage, for example, or mixed genres. These are questions that were in the air or in my mind last year; artists were also beginning to wonder what would happen in 2016, so those ideas all came together.”

O’Reilly says reflecting on the Rising is also a good opportunity to explore how writers are engaging with social change today. In his editorial, he asks: “Can we rekindle any of the energy of that time and use it for ourselves as we look for a better way of organising this society?”

In the special 1916 issue, O’Reilly, who grew up in Derry, recounts his own experience of the first time he saw the Proclamation, in the home of Patsy O’Hara, who had died on hunger strike. The young Seán was waiting in a queue of mourners with his father and describes how he found himself reading “this creepy stained page trapped in a gold metal-work frame”.

What does he feel when he reads the Proclamation now? “Words must grow and change with us. No document is static — you bring yourself to it and you re-read, reigniting the words as you read them. I’d like to think the poets who had a hand in that document would have wanted the words to remain fresh and not have a fixed meaning — that it’s not a dead text, that it has to be kept alive.”

O’Reilly points to the contradiction inherent in the fact that copies of the Proclamation have been sent to every school in the country, while at the same time, history has been removed as a compulsory subject on the curriculum.

“I found that staggering. I’m amazed it hasn’t gotten more attention. I’ve heard parents talk about their children and the Tricolour and the Proclamation, but I haven’t heard anyone talk about the fact that their children may not read any history.”

Irish history was literally a no-go subject when O’Reilly was in school in Derry. “We weren’t allowed to touch Irish history — it finished with Brian Boru, nothing happened after that. I heard about the 1916 Rising at home.

“We were going to schools through riots and hunger strikes but we weren’t allowed to talk about it. We spent our time studying shipbuilding in northern England, or wheat-growing in Saskatchewan. At the time it was just the way things were, you couldn’t wait to leave. It was all you thought about. It was later when I started looking back that I realised what was going on — the silence was incredible.”

The Stinging Fly has been to the forefront of the resurgence in literary journals, publishing award-winning collections from writers including Kevin Barry, Mary Costello, and Colin Barrett. O’Reilly’s novel, Watermark, was the first publication of the Stinging Fly Press imprint. To what does O’Reilly attribute this renewed appetite for Irish writing?

“I call it a return to stillness; people are slowing down. They’re trying to keep that unique experience of stillness, of silence. All you can do is hope but I don’t think there’s anybody who could be negative about what’s happening in Irish writing. It’s happening all around us.”

In the Wake of the Rising is launched today. See www.stingingfly.org

Inspired by family tales of Black and Tans in Cork

Writer Martina Evans has been living and working in London for almost two decades but her home place of Cork still informs much of her work.

“I think that childhood is when your most intense experiences happen. Margaret Atwood said we write because the dead want blood. In a lot of The Stinging Fly pieces you can see the fascination with the dead.”

Evans’ contribution to The Stinging Fly special Rising issue, the short story ‘Now We Can Talk Openly About Men’, is set in Mallow and Cork city at the time of the War of Independence and is told from the point of view of a dressmaker whose daughter is going out with an officer in the Auxiliaries.

“I became a writer after my father died. He was born in 1902, and he and his brother were taken hostage by the Tans. My mother spoke about it but my father never did, and I think at a certain age that becomes very interesting to you.

“The fact that my father said absolutely nothing haunts me now but for a lot of my generation, growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, a lot of that stuff, Irish language and so on, was conservative and boring. It was too near us. It’s different now.”

Evans, who grew up in Burnfort, near Mallow, started writing full-time after working as a radiographer for 15 years and now teaches creative writing. Her interest in the role of women in the Republican struggle came to the surface in the late 1990s, when she began researching a novel on the subject.

“I was thinking of writing about my grandmother, who had been in the Land League in 1881.

“I was working on the novel but I couldn’t really understand Republican women — I found them fascinating but I couldn’t understand how they operated, because that idealism, we don’t see it like that any more.

“When I went to Kilmainham [Gaol], I didn’t expect it to have a visceral effect on me but I started crying, listening to the story of Ann Devlin [Robert Emmet’s housekeeper] and seeing how men had political status but women didn’t.

“I thought of my aunt who was in prison, and, according to family legend, refused to drink from a tin cup, and insisted on having a china cup.”

Evans got the title of the story from her late mother, who she describes as a “great character”.

“I was just divorced and we were in the kitchen with her friends and she said, ‘we’re all widows here and Martina is divorced, so we can talk openly about men’.

“When she said it I was thinking I was going to be initiated or we’d get broomsticks and fly off or something.”