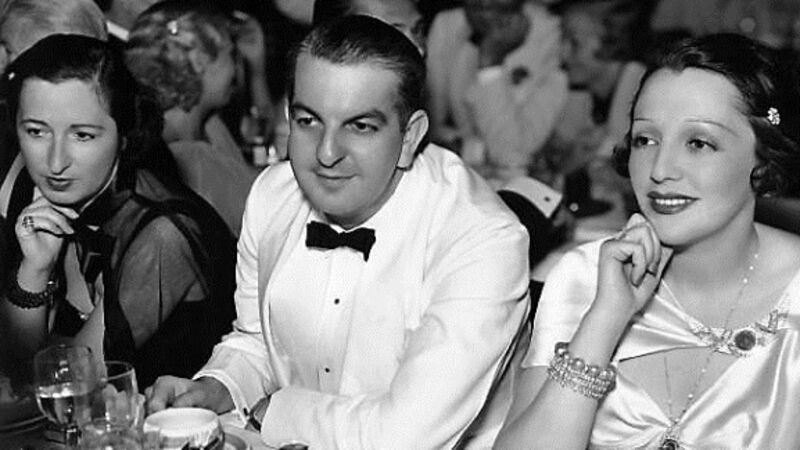

An untold Hollywood story - Costume designer Orry George Kelly had a central role in Hollywood’s golden age

Orry George Kelly was born in small-town coastal Australia in 1897. Unless you’re a movie historian, the name may not mean much - unlike Ingmar Bergman’s trench coat in Casablanca, Marilyn Monroe’s famous nudey bead dress in Some Like It Hot, or pretty much any film costume worn by Bette Davis. Orry-Kelly — as he renamed himself professionally, inserting a hyphen and dropping the George — was the designer of these iconic costumes. He was considered a visionary — his emphasis being on silhouette, colour, and form — and female movie stars clamoured for his designs. When he was fired at one point in his career, Bette Davis insisted he be reinstated.

For decades, he was Australia’s most prolific Oscar winner, gaining three Academy Awards for costume design, being surpassed only in 2014 by Catherine Martin, who designed for Moulin Rouge and Gatsby. So why does Orry-Kelly remain, over half a century after his death, one of Hollywood’s untold stories? Why did he fall into obscurity, despite his central role in Hollywood’s golden age, and why, after all these years, are we hearing about him now?