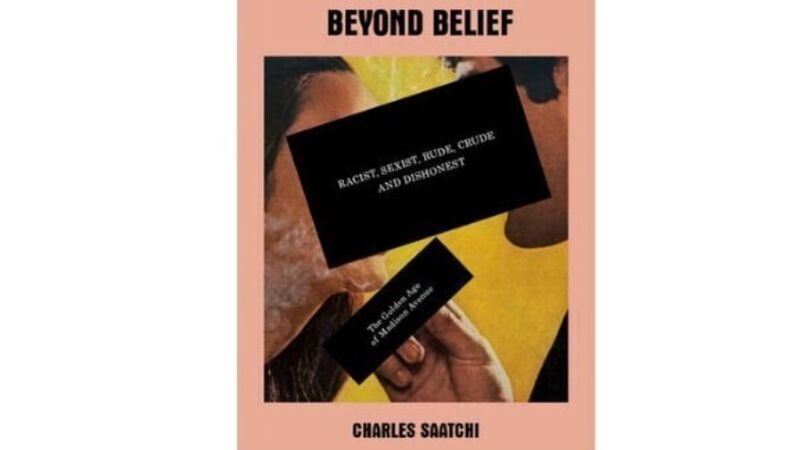

Book review: Beyond Belief

LIFE magazine was a pillar of America’s cultural life in the 1950s. The world’s best photographers, including Robert Capa, ran their photos in it. President Harry S Truman chose the magazine to serialise his memoirs. It was an arbiter of taste. Celebrities like Marilyn Monroe adorned its covers. It set the tone for the nation.

In 1952, the magazine ran an advertisement by Chase & Sanborn, a coffee company that later merged with Nabisco, about the merits of its product. It shows a man seated on a wooden kitchen chair. He’s dressed for the office in white shirt, braces, pants and tartan-patterned socks. He’s a man who might need a strong cup of coffee in the morning.