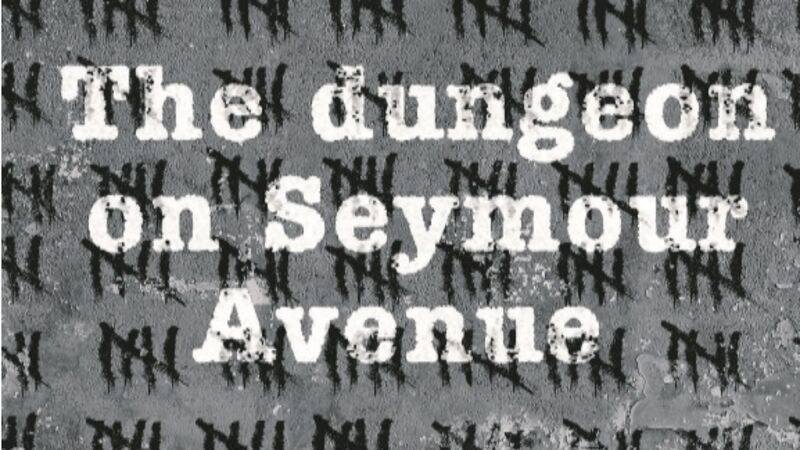

THE LONG READ: The Dungeon on Seymour Avenue

A young woman walked into a Family Dollar store in the US city of Cleveland, exhausted, sweaty and desperate. Michelle Knight was 21 and she’d spent the past few hours searching for the location of a crucial meeting. The appointment, with social services, was to discuss how she might regain custody of her two-year-old son, who’d been placed in foster care a few months earlier after her mother’s boyfriend got drunk and, Knight says, became abusive and broke the boy’s leg.

It was August 2002 — years before smartphones and Google Maps — and after nearly four hours of wrong turns, Knight spotted the Family Dollar store. She bought a soft drink and started asking people for directions. A woman in the aisle couldn’t help. The cashier couldn’t either. Knight was about to walk out when she heard a male voice: “I know exactly where that is.” She looked up and saw a man with thick, messy hair and a potbelly, dressed in black jeans and a stained flannel shirt.