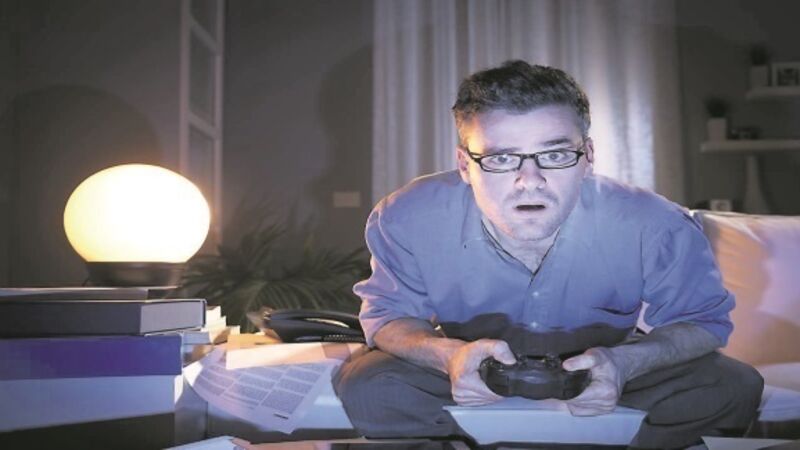

When the game is controlling you

Swimming with dolphins is typically viewed as a serene method of being at one with nature, sharing time and space with a smiley, bottle nosed mammal. It’s joyful and thrilling. Except, not always.

Alright - my dolphin experience isn’t quite of the Jacques Cousteau variety. Instead, it was via interminable, thumb-numbing sessions on my Sega Megadrive as I tried and repeatedly failed to finish Ecco the Dolphin, an action-adventure game that often pushed my adolescent blood pressure through the roof. As a relatively mild-mannered teenager more interested in football, music and being routinely ignored by any girls I fancied, the maddening, addictive quality of gaming brought with it the realisation that maybe this wasn’t a good relationship. When, in blundering on the penultimate stage of the game for the umpteenth time, I plucked the cartridge from the console and actually starting shouting at it, I realised that I needed to step away.