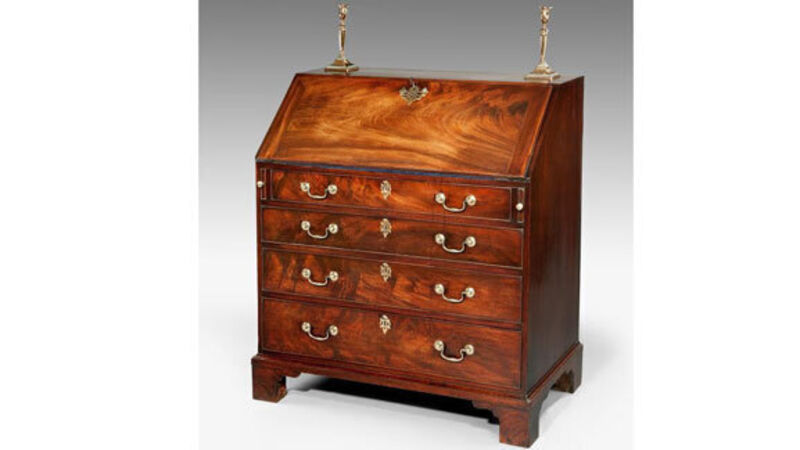

Vintage view: Georgian mahogany

LIDE your fingers over the silken finish of a ruby rich piece of Georgian mahogany, and you can feel that first flush of pleasure an entitled gentleperson of the 18th century may have experienced on delivery of their new writing desk or dining table.

Tropical hardwoods have an unsettling history, and mahogany has a sombre story embedded in its very name. It’s a wonder that a mini-series framed around the intrigues of the trade in precious trees has yet to hit the small screen in a luscious period drama.