The end of innocence

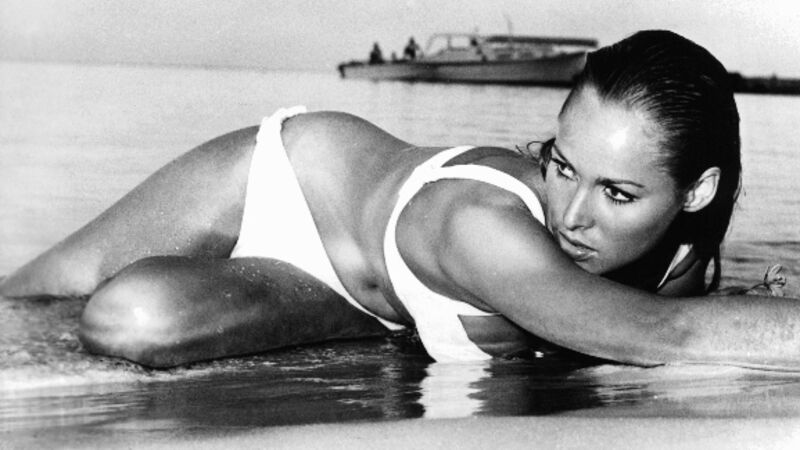

Andrew Cook, who will publish a book entitled 1963: That Was the Year That Was next month, says the average year has two or three big news stories; in 1963, there were more than 30: the graphic self-immolation of a Buddhist monk in Saigon, a harbinger of horrors to come in Vietnam; the Moors Murders; Valentina Tereshkova — the first woman in space; Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech; and the release of Dr No, the first James Bond movie, among them. The year also marked the end of innocence.

“It’s a real watershed year,” says Cook. “Preconceptions about life were shattered. The average person in 1963 would never have questioned that British intelligence would sell out their country. That year there were a whole string of intelligence scandals where moles — such as Kim Philby — betrayed the Ministry of Defence.