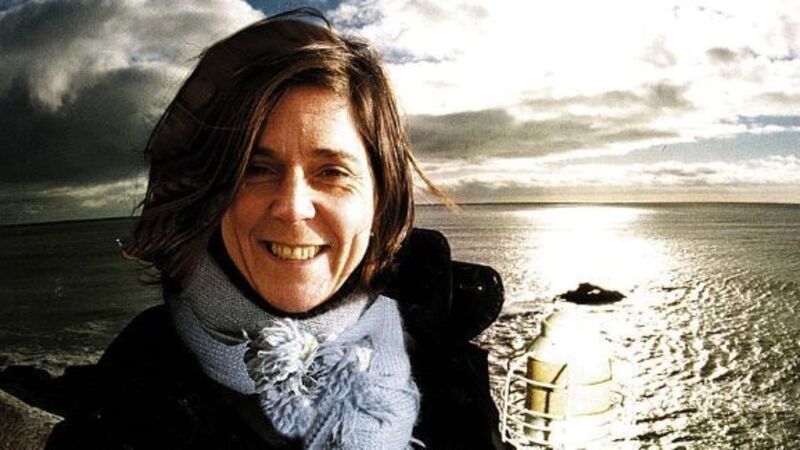

Doing her homework

ARTIST Dorothy Cross’s formative years in Cork have inspired some of her best-known work. In her latest project, the two books, Montenotte and Fountainstown, Cross examines her father’s photographs of the places where she grew up.

Occasional Press, a specialised publisher run by Jim Savage and David Lilburn, proposed the project. The two books evolved out of their discussions. Ballynahinch Castle, Connemara, was a financial partner.