Colman Noctor: Classic stories show children how to survive in the face of adversity

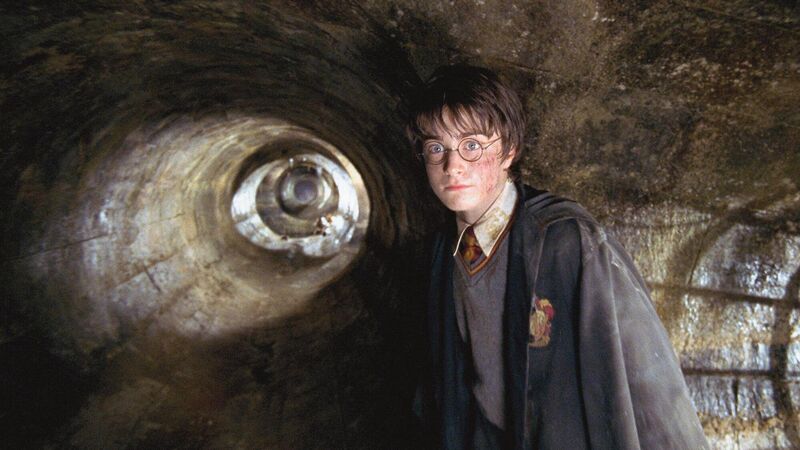

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets: classic stories have much to teach

The Harry Potter movie franchise turned 20 last week. I am not ashamed to say that despite being 44 years old, I have always been, and will always remain, a huge fan of the books and movies.

Like many others, I was enthralled by JK Rowling's characters and storylines. I can remember queuing outside Eason’s in Liffey Valley at midnight in July 2007 to get my copy of and, despite being surrounded by teenagers in wizard outfits, I stuck it out to be one of the first to read it.