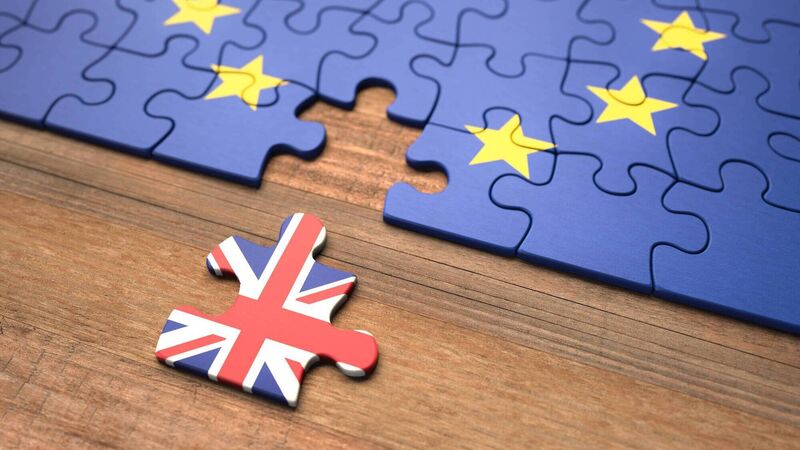

History repeats itself. Spanish Flu and Covid 19, Economic War and Brexit?

Brexit negotiations have stalled, with the two key stumbling blocks being access to British fishing waters and the EU’s demand that the UK tie itself closely to the bloc’s state aid, labour and environmental standards, to ensure it does not undercut the EU’s Single Market.

While Covid-19 has occupied national headlines for the past six months, the countdown to Britain leaving the EU continues to ebb away, with just 18 weeks left.